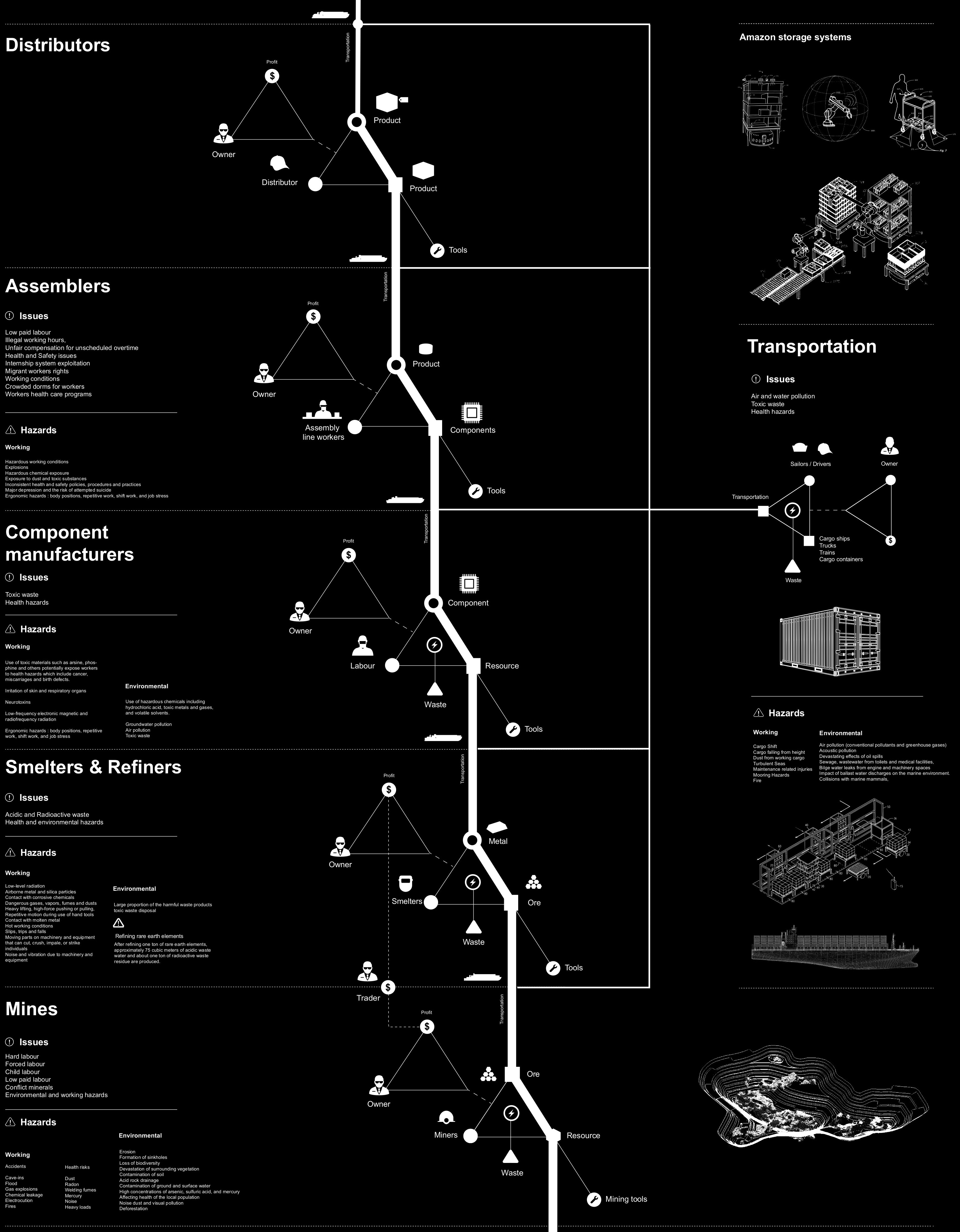

In his book A Geology of Media, Jussi Parikka suggests that we try to think of media not from Marshall McLuhan’s point of view — in which media are extensions of human senses — but rather as an extension of Earth. Media technologies should be understood in context of a geological process, from the creation and the transformation processes, to the movement of natural elements from which media are built. Reflecting upon media and technology as geological processes enables us to consider the profound depletion of non-renewable resources required to drive the technologies of the present moment. Each object in the extended network of an AI system, from network routers to batteries to microphones, is built using elements that required billions of years to be produced. Looking from the perspective of deep time, we are extracting Earth’s history to serve a split second of technological time, in order to build devices that are often designed to be used for no more than a few years.... From a slow process of elemental development, these elements and materials go through an extraordinarily rapid period of excavation, smelting, mixing, and logistical transport — crossing thousands of kilometers in their transformation. Geological processes mark both the beginning and the end of this period, from the mining of ore, to the deposition of material in an electronic waste dump. For that reason, our map starts and ends with the Earth’s crust. However, all the transformations and movements we depict are only the barest anatomical outline: beneath these connections lie many more layers of fractal supply chains, and exploitation of human and natural resources, concentrations of corporate and geopolitical power, and continual energy consumption. [†]One illustration of the difficulty of investigating and tracking the contemporary production chain process is that it took Intel more than four years to understand its supply line well enough to ensure that no tantalum from the Congo was in its microprocessor products. As a semiconductor chip manufacturer, Intel supplies Apple with processors. In order to do so, Intel has its own multi-tiered supply chain of more than 19,000 suppliers in over 100 countries providing direct materials for their production processes, tools and machines for their factories, and logistics and packaging services.... Dutch-based technology company Philips has also claimed that it was working to make its supply chain ‘conflict-free’. Philips, for example, has tens of thousands of different suppliers, each of which provides different components for their manufacturing processes. Those suppliers are themselves linked downstream to tens of thousands of component manufacturers that acquire materials from hundreds of refineries that buy ingredients from different smelters, which are supplied by unknown numbers of traders that deal directly with both legal and illegal mining operations. In The Elements of Power, David S. Abraham describes the invisible networks of rare metals traders in global electronics supply chains: “The network to get rare metals from the mine to your laptop travels through a murky network of traders, processors, and component manufacturers. Traders are the middlemen who do more than buy and sell rare metals: they help to regulate information and are the hidden link that helps in navigating the network between metals plants and the components in our laptops.”[†]

|

Assemblers

! Issues

! Hazards

Working

Component manufacturers

! Issues

! Hazards

Working

Environmental

Smelters & Refiners

! Issues

! Hazards

Working

Environmental

⚠

Refining rare earth elements

Mines

! Issues

! Hazards

Working

Environmental

|

|