"Licensing a nuclear power plant is in my view, licensing random

premeditated murder. First of all, when you license a plant, you know

what you’re doing—so it’s premeditated. You can’t say, "I didn’t

know." Second, the evidence on radiation-producing cancer is beyond

doubt. I’ve worked fifteen years on it [as of 1982], and so have many

others. It is not a question any more: radiation produces cancer,

and the evidence is good all

the way down to the lowest doses."

The following is chapter 4 from the 1982 paperback edition of the book

Nuclear

Witnesses, Insiders Speak Out and is an interview with Dr. John

Gofman detailing his personal

experiences and knowledge regarding the nuclear establishment. Dr. Gofman

is a Professor Emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley (Ph.D. in

nuclear-physical chemistry and an M.D.) who was the first Director of the

Biomedical Research Division of the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory from

1963-65 and one of nine Associate Directors at the Lab from 1963-1969. He was

involved in the Manhattan Project and is a co-discoverer of Uranium-232,

Plutonium-232, Uranium-233, and Plutonium-233, and of slow and fast neutron

fissionability of Uranium-233. He also was a co-inventor of the uranyl

acetate and columbium oxide processes for plutonium separation. He has

taught in the radioisotope and radiobiology fields from the 1950s at least

up into the 1980s, and has done research in radiochemistry, macromolecules,

lipoproteins, coronary heart disease, arteriosclerosis, trace element

determination, x-ray spectroscopy, chromosomes and cancer and radiation

hazards. Starting in 1969 he began to challenge the AEC claim that there

was a "safe threshold" of radiation below which no adverse health effects

could be detected.

Chapter 4 of Nuclear Witnesses outlines Gofman’s career

history and how, over time, he came to understand the true dangers

of artificial, man-made radioactive matter and how the government,

and the people in charge of the nuclear industry, were suppressing

the facts of this danger from humankind. This book provides a

wealth of information about the radioactive contamination of Mother

Earth by the nuclear industry since the 1940s.

Quoting the book’s author Leslie Freeman, "It is the premise

of this book that if the American people knew the truth about radiation

there would be no nuclear issue." The myth is that there is a "safe

threshold" of exposure to radioactive material, a permissible does below

which no health effects can be detected. Who’s interests are being

served here? Who benefits? Certainly not people being

dosed!

"My particular combination of scientific credentials is very handy in the

nuclear controversies, but advanced degrees confer no special expertise in

either common sense or morality. That’s why many laymen are better

qualified to judge nuclear power than are the so-called experts." Gofman

has achieved the singular distinction of being branded "beyond the pale of

reasonable communication" by the nuclear power industry.

—from

IRREVY,

An Irreverent, Illustrated View of Nuclear

Power, 1979, by Dr. John Gofman.

— ratitor

Begin Excerpts from Chapter 4

[text in italics denotes the author’s—Leslie Freeman’s—voice.]

Gofman sits back. It is the attempt to deceive the public that

makes him so angry. His reaction was the same when he learned how the

Atomic Energy Commission was deceiving the public about the effects of

low-level radiation. When the AEC tried to censor his findings about

radiation-induced cancers, Gofman reached his turning point. To him,

censorship is "the descent of darkness.". . .

Then I started hearing that there were a lot of people from the

electric utility industry who were insulting us and our work. They

were saying our cancer calculations from radiation were ridiculous,

that they were poorly based scientifically, that there was plenty of

evidence that we were wrong. Things like that. So I wondered what

was going on there. At that point—January 1970—I hadn’t said

anything about nuclear power itself. In fact, I hadn’t even thought

about it. It was stupid not to have thought about it. I just

wondered, Why is the electric utility industry attacking us?

I began to look at all the ads that I had just cursorily seen in

"Newsweek" and "Time" and "Life," two-page spreads from the utilities,

talking about their wonderful nuclear power program. And it was all

going to be done "safely," because they were never going to give

radiation above the safe threshold.

And I realized that the entire nuclear power program was based on a

fraud—namely, that there was a "safe" amount of radiation, a

permissible dose that wouldn’t hurt anybody. . . .

"Someone from the AEC came to my house last weekend," he said. "He

lives near me. And he said, ‘We need you to help destroy Gofman and

Tamplin.’ And I told him you’d sent me a copy of your paper, and I

didn’t necessarily agree with every number you’d put in, but I didn’t

have any major difficulties with it either. It looked like sound

science. And—you won’t believe this—but do you know what he said to

me? He said, ‘I don’t care whether Gofman and Tamplin are right or

not, scientifically. It’s necessary to destroy them. The reason is,’

he said, ‘by the time those people get the cancer and the leukemia,

you’ll be retired and I’ll be retired, so what the hell difference

does it make right now? We need our nuclear power program, and

unless we destroy Gofman and Tamplin, the nuclear power program is in

real hazard from what they say.’. . .

. . . in 1972 the National Academy of Sciences published a report

called the BEIR Report—Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation—a

long, thick report, in which they walked around the problem as best

they could, and finally concluded that we were too high between four

and ten times. But if you read the fine print, they were admitting

that we might just be right.[22]

When that came out, everybody realized that the AEC was not worth a

damn. By then the AEC had gotten themselves into another flap. Henry

Kendall and Dan Ford of the Union of Concerned Scientists showed that

the AEC didn’t know whether the Emergency Core Cooling System would

ever work or wouldn’t.[23] The Emergency Core Cooling System was the

last barrier of safety in a major nuclear accident. This further

damaged the credibility of the AEC.

Those two events—the conflict with Ford and Kendall and the

conflict with us—finally led them to realize they could no longer use

the words "Atomic Energy Commission," and so the government abolished

the AEC.

"We are now solving the problem," they said. "We’ll create two new

agencies—ERDA (Energy Research and Development Agency) and NRC

(Nuclear Regulatory Commission)."

ERDA was supposed to promote the development of atomic energy, and

NRC was supposed to concern itself with public safety. The idea was

that it was the promotion of nuclear energy that made the AEC’s safety

work so poor. The new NRC was only supposed to involve itself in

safety—no promotion.

Which turned out to be one of the greatest lies in history. . . .

I had made one mistake. If the Department of Energy or the AEC

gives you money on a sensitive subject, they don’t mean for you to

take the job seriously. They need you—with your scientific

prestige—so they can point to you. "We have so and so studying the

problem." Studying the problem is marvelous. But if you want the

money and the continued support, you should go fishing or play golf.

My mistake was I discovered something. . . .

Gofman decided to take an early retirement at the age of fifty-five,

so he gave up his position at the University in 1975 and became

professor emeritus. Although no longer engaged in active teaching,

Gofman did not give up research. In the next years he discovered that

plutonium was even more hazardous than he had thought. "Plutonium is

so hazardous that if you had a fully developed nuclear economy with

breeder reactors fueled with plutonium, and you managed to contain the

plutonium 99.99 percent perfectly, it would still cause somewhere

between 140,000 and 500,000 extra lung-cancer fatalities each year.". .

The requirement for controlling plutonium in a nuclear economy

built on breeder reactors would be to lose no more than one millionth

or ten millionth of all the plutonium that is handled into the

environment where it could get to people. Which brings up a

fundamental thing in nuclear energy—there are some engineers,

scientists, who are not merely fraudulent sycophants of the system.

They’re really out of touch with reality.

I was once on an airplane with a strong pronuclear engineer. I

said, "I’ve done some new work on plutonium. I think it’s a lot more

toxic than had been thought before. At what toxicity would you give

up nuclear power?"

He said, "What are you talking about?"

"If I told you that you had to control your plutonium losses at all

steps along the way—burps, spills, puffs, accidents, leaks,

everything—that you can’t afford to lose even a millionth of it,

would that cause you to give up nuclear power?"

"Oh, I understand your point now, John," he said. "Now, you tell

me—we look to biologists like you to tell us how well we need to do.

If you say I’ve got to control it to one part in ten million, we’ll do

it. If you say it’s got to be one in a billion or ten billion we’ll

do it. You tell us what we have to engineer for, and we’ll do it."

I said, "My friend, you’ve lost touch with reality completely.

I’ve worked in chemistry laboratories all my life, and to think you

can control plutonium to one in a million is absolutely absurd. If

you were a patient of mine who came in to see me, I’d refer you to a

psychiatrist."

"Well, John, engineering is my field. And we believe we can do

anything that’s needed."

Engineers do believe that. That’s the arrogance of engineers—they

think they can do anything. Now their mistakes catch up with them, as

you see from the DC-10s and the Tacoma Narrows Bridge that fell down,

and the Teton Dam and the most recent episode, Three Mile Island—where

the unthinkable, the impossible, did happen.

Nuclear Power: A Simple Question

Many people think nuclear power is so complicated it requires

discussion at a high level of technicality. That’s pure nonsense.

Because the issue is simple and straightforward.

There are only two things about nuclear power that you need to

know. One, why do you want nuclear power? So you can boil water.

That’s all it does. It boils water. And any way of boiling water

will give you steam to turn turbines. That’s the useful part.

The other thing to know is, it creates a mountain of radioactivity,

and I mean a mountain: astronomical quantities of strontium-90 and

cesium-137 and plutonium—toxic substances that will last—strontium-90

and cesium for 300 to 600 years, plutonium for 250,000 to 500,000

years—and still be deadly toxic. And the whole thing about nuclear

power is this simple: can you or can’t you keep it all contained? If

you can’t, then you’re creating a human disaster.

You not only need to control it from the public, you also need to

control it from the workers. Because the dose that federal

regulations allow workers to get is sufficient to create a genetic

hazard to the whole human species. You see, those workers are allowed

to procreate, and if you damage their genes by radiation, and they

intermarry with the rest of the population, for genetic purposes it’s

just the same as if you irradiate the population directly.[27]

So I find nuclear power this simple: do you believe they’re going

to do the miracle of containment that they predict? The answer is

they’re not going to accomplish it. It’s outside the realm of human

prospects.

You don’t need to discuss each valve and each transportation cask

and each burial site. The point is, if you lose a little bit of it—a

terribly little bit of it—you’re going to contaminate the earth, and

people are going to suffer for thousands of generations. You have two

choices: either you believe that engineers are going to achieve a

perfection that’s never been achieved, and you go ahead; or you

believe with common sense that such a containment is never going to be

achieved, and you give it up.

If people really understood how simple a problem it is—that

they’ve got to accomplish a miracle—no puffs like Three Mile

Island—can’t afford those puffs of radioactivity, or the squirts and the

spills that they always tell you won’t harm the public—if people

understood that, they’d say, "This is ridiculous. You don’t create

this astronomical quantity of garbage and pray that somehow a miracle

will happen to contain it. You just don’t do such stupid things!"

Licensing a nuclear power plant is in my view, licensing random

premeditated murder. First of all, when you license a plant, you know

what you’re doing—so it’s premeditated. You can’t say, "I didn’t

know." Second, the evidence on radiation-producing cancer is beyond

doubt. I’ve worked fifteen years on it, and so have many others. It

is not a question any more: radiation produces cancer, and the

evidence is good all the way down to the lowest doses.

The only way you could license nuclear power plants and not have

murder is if you could guarantee perfect containment. But they admit

that they’re not going to contain it perfectly. They allow workers to

get irradiated, and they have an allowable dose for the

population.[28] So in essence I can figure out from their allowable

amounts how many they are willing to kill per year.

I view this as a disgrace, as a public health disgrace. The idea

of anyone saying that it’s all right to murder so many in exchange for

profits from electricity—or what they call "benefits" from

electricity—the idea that it’s all right to do that is a new advance

in depravity, particularly since it will affect future generations.

You must decide what your views are on this: is it all right to

murder people knowingly? If so, why do you worry about homicide? But

if you say, "The number won’t be too large. We might only kill fifty

thousand—and that’s like automobiles"—is that all right? . . .

People like myself and a lot of the atomic energy scientists in the

late fifties deserve Nuremberg trials. At Nuremberg we said those who

participate in human experimentation are committing a crime.

Scientists like myself who said in 1957, "Maybe Linus Pauling is right

about radiation causing cancer, but we don’t really know, and

therefore we shouldn’t stop progress," were saying in essence that

it’s all right to experiment. Since we don’t know, let’s go ahead.

So we were experimenting on humans, weren’t we? But once you know

that your nuclear power plants are going to release radioactivity and

kill a certain number of people, you are no longer committing the

crime of experimentation—you are committing a higher crime.

Scientists who support these nuclear plants—knowing the effects of

radiation—don’t deserve trials for experimentation; they deserve

trials for murder. . . .

. . . The only solution is, you must stop all efforts to develop

first-strike force solutions everywhere—whether they be nuclear or

other—and move toward a more just society.

Even if you made an agreement to abolish all nuclear weapons, but

you left established power structure in the U.S. and the USSR, they’d

go on to research mind control or some chemical or biological thing.

My view is, there exists a group of people in the world that have a

disease. I call it the "power disease." They want to rule and

control other people. They are a more important plague than cancer,

pneumonia, bubonic plague, tuberculosis, and heart disease put

together. They can only think how to obliterate, control, and use

each other. They use people as nothing more than instruments to cast

aside when they don’t need them any more. There are fifty million

people a year being consumed in a nutritional holocaust around the

world; nobody gives a damn about starvation. If fifty million white

Westerners were dying, affluent Western society would worry, but as

long as it’s fifty million Third World people dying every year, it

doesn’t matter.

In my opinion, what we need is to move toward being nauseated by

people who want to be at the top, in power. Can you think of anything

more ridiculous than that the Chinese, Russian, and American people

let their governments play with superlethal toys and subject all of us

to these hazards? The solution is not to replace one leader with

another or to have more government. Society has to reorganize itself.

The structure we have now is, the sicker you are socially, the more

likely it is that you’ll come out at the top of the heap.

* * * * * * * * *

Author’s Note

Two things happened that led me to write this book. First, a

doctor tried to convince me to take radioactive iodine for an

overactive thyroid. I refused. Several months later John Gofman told

me I was very fortunate. The radioactive iodine, he explained, would

have increased the chance of my getting cancer by more than 100

percent.

The other thing that led me to write this book was the accident at

Three Mile Island. Coincidentally, my thyroid condition had been

diagnosed the same week that Three Mile Island vented radioactive

gases into the atmosphere. I read everything I could lay my hands on,

groping for the truth behind the evasive reports published by the

Nuclear Regulatory Commission. I finally read verbatim transcripts of

the Commissioners’ meeting held the day after the accident. The words

these men said to each other stunned me. They had no idea what was

happening and no idea how to stop it. And meanwhile they were issuing

reassuring reports to the public.

I wanted the truth. For the first time I felt my survival was at

stake—nuclear power was not an abstract issue: it was a matter of

life and death. I started to talk to people—scientists, doctors,

nuclear workers.

I interviewed twenty-four people who have worked with or around

nuclear materials. In nineteen cases I traveled to the person’s home

or place of work. Most interviews took between two and four hours and

were followed up by phone interviews. I taped the in-person and

telephone interviews and listened to them several times, taking notes.

I then selected and transcribed those which I felt contained the

clearest and most important information and were also the most

fascinating as narratives. These were the transcripts from which I

worked for the chapters of this book.

A word about the editing I did. In every case I tried to maintain

the exact words, the exact flavor of the speech, and the exact meaning

intended by the speaker. I have cut out sections that were redundant,

irrelevant, unnecessary, or confusing. The repetitive "you know" or

"like I said" was eliminated when it seemed too distracting—appropriate

perhaps in conversation but not on the page.

Each chapter was returned to the narrator in draft form for

comments, accuracy, and approval. In some cases a name was changed to

protect an informant, an expression was changed, a statistic was

corrected.

The final version of each chapter was then written—including an

introductory section, footnotes, and a bibliography of sources

relevant to the chapter. Each narrator was also asked for a

photograph to include with his or her chapter.

The question that I asked initially in each interview was about

personal background. This was followed by a series of questions about

what experiences the person had which made him or her change or

develop a point of view on nuclear power. I did not merely listen.

When I did not understand, I asked questions. When I did not believe

something, I said so. I asked for proof, for reasons, for the

thoughts and feelings which made people act the way they did. I asked

them to describe experiences in such a way that I could see what they

saw and hear what people said and did. They described specific

hearings and meetings. Again and again I asked to be told what went

through their minds as they experienced the things they told me about.

It was these personal moments that most brought me into their lives

and that I have attempted to bring to the reader.

It is the premise of this book that if the American people knew the

truth about radiation there would be no nuclear issue. The

information speaks for itself. In this book people who have had

direct personal experience with the nuclear establishment speak about

what they learned. They did not necessarily start out as proponents

or opponents of nuclear power; they are people who have in common a

genuine respect for hard work. In almost every case they found their

integrity as workers threatened by involvement with the nuclear

establishment. When they mentioned that something was done sloppily,

that some regulation was being violated, that something was dangerous,

their concerns were ignored, trivialized, rationalized, or twisted.

Some, unable to work under such conditions and feeling their sense of

decency outraged and their survival in jeopardy, began to speak

publicly. Then they found out what they were up against: it wasn’t

just their boss, it wasn’t just their boss’s boss: it was the union,

the utility company, the military-industrial complex that were

insisting on the myth that nuclear power was "safe." No one was

permitted to challenge this myth and retain credibility. Nuclear

energy existed for the "benefit" of the people and nuclear weapons

were necessary for "national security."

The stories in this book are evidence that even in the face of

intimidation, people still believe their own experience matters and

that other people matter. They are concerned about the lives of their

children and the continuation of the species. These people know that

when people hear the truth, they listen.

Begin Chapter 4

The following is taken from the 1982 paperback edition of

Nuclear Witnesses,

Insiders Speak Out, by Leslie J. Freeman, © 1981 by

W W Norton & Company,

and is reprinted here with written permission from the publisher.

CHAPTER 4

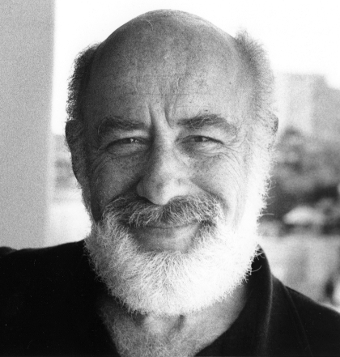

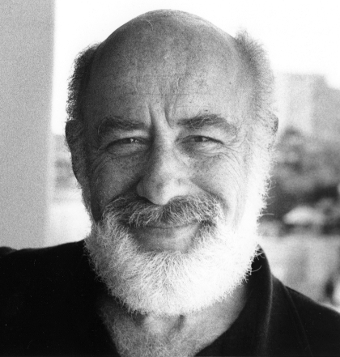

John W. Gofman, Medical Physicist

A cool, crisp morning, late in August 1979. From inside a

meticulously furnished living room in the quaint house, built high on

a hill overlooking the city of San Francisco, you can see the city

orange and white, glittering in the distance.

John Gofman sits across from me on a wooden bench-sofa built into

the corner of the living room. He lights a pipe and crosses his legs.

On the verge of sixty, he is surprisingly youthful. His oval-shaped

face is framed with a thick snow-white beard. His skin is ruddy and

smooth, his eyes quick, piercingly alive.

As usual, I begin the interview by explaining what led me to write

this book. I tell him about discovering I had an overactive thyroid

and the thyroid specialist who recommended radioactive iodine as a

cure. Gofman’s eyes narrow. He leans forward. "Did you take the

radio-iodine?" I shake my head no and explain, "I was afraid of it."

"Let me tell you what that would have done to you," he says. His

voice rises in anger as he explains that the dose the specialist said

he wanted to give me would have increased my chances of developing

cancer by "50 to 100 percent—which is a massive increase!" Gofman

sits back and relights his pipe. Then he continues, warming to the

subject: "The logical question is: if what I say is true, then how

come the medical profession doesn’t know it? Well, there are many

reasons, some of which don’t even surface. For example, hundreds of

thousands, perhaps a few million people have been given radio-iodine

treatments already. Think of how hard it is for the physician to

think that his profession can have endangered the lives of five

hundred thousand to a million people. So psychologically he has a

wall that says, ‘No, this cannot be harmful. I personally have not

seen a single cancer from it.’ Which of course is a ridiculous way to

look at it.

"The Public Health Service sponsored a follow-up study of some

30,000 people who had received radio-iodine. Came to the conclusion

that it didn’t appear that cancer was seriously increased. Absolutely

rotten, miserable, stupid, unscientific study. Published in a quality

medical journal—but that didn’t in any way prevent it from being all

those things—unscientific, miserable, and stupid. What was wrong

with that study? First of all, we know that very few cancers surface

before ten years after the radiation. Then they get more and more

frequent. In the study the average person was followed up only nine

years. In other words, they were studying the people in the period

when you don’t expect cancers to occur!

"Also, the number of radiation-induced cancers goes up in

proportion to how frequent that particular cancer type is anyway.

Breast cancer is 20 percent of all cancer in women. So after you have

treated women of twenty-five or so with radio-iodine, you should look

in the fifty-year age bracket, when breast cancer becomes a common

disease. So the whole damn study, averaging nine years of follow-up,

is at the wrong time and is giving a false impression of security

that’s going to kill more and more people.

"The epidemic of doctor-induced cancer from radio-iodine is ahead

of us yet!

"You would think that medicine would have become wiser from the

experience with asbestos, with vinyl chloride, with radiation. But

they don’t seem to learn from such experience. They seem to think

that radio-iodine is something special. The next thing will be

radio-strontium is something special. Then plutonium is special.

"I’ll sit here and confidently say into your recorder—and if you

hold the tape for another ten years, I will still be confirmed. I

don’t say many things positively. A lot of things I’ll tell you I

don’t know—we’re uncertain, more work needs to be done. But on this

one I don’t put any of those qualifiers in. It is going to occur.

The dose to the body from radio-iodine at therapeutic levels is such

that it’s going to produce many, many cancers. Then it’s going to be:

‘Oh, we must not use radio-iodine any more. At the time we did it, it

was the best medical practice.’

"See, that’s the out. If the whole profession was idiotic in a

given time and agreed to the idiot position, that’s regarded as the

‘best medical practice of the time.’ That’s the story."

Gofman sits back. It is the attempt to deceive the public that

makes him so angry. His reaction was the same when he learned how the

Atomic Energy Commission was deceiving the public about the effects of

low-level radiation. When the AEC tried to censor his findings about

radiation-induced cancers, Gofman reached his turning point. To him,

censorship is "the descent of darkness."

"I’m not interested in being a crusader," Gofman says, "but

somebody had to say something about this issue, so why not me?"

The Beginning: Uranium-233

Born in Ohio, John Gofman grew up in Cleveland and attended Oberlin

College, with a major in chemistry. He thought he might like to do

medical research, so in his junior and senior years he took courses to

qualify him for medical school. After graduating from Oberlin 1939

with an A.B. in chemistry, Gofman entered Western Reserve University

Medical School. Although he enjoyed learning medicine and did quite

well his first year there, he realized he was not getting the sound

scientific background in physical sciences that he would need for

medical research. In 1940 Gofman took a leave of absence from medical

school and enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley as a

Ph.D. candidate in chemistry. "The first thing you did when you came

to Berkeley as a Ph.D. candidate was to choose a research field. I

looked around and there was a young professor there by the name of

Glenn Seaborg, who was working in artificial

radioactivity."[1] Glenn Seaborg was the scientist

who discovered plutonium,[2] the man-made

radioactive element that would be used five years later in the atomic

bomb dropped on Nagasaki (9 August 1945).

I thought, probably all kinds of biochemical problems in medicine

are going to be solved by the application of radioactive tracers.[3]

How better could I prepare myself for a future medical career than to

work on a problem involving artificial radioactivity?

So I elected to work with Glenn Seaborg. He assigned me a

problem—there was a possibility from thorium you might be able to

make a substance called uranium-233, provided it existed, and we

didn’t know whether it would exist or not.

He said, "Why don’t you see if you can find out whether it exists

or not?"

It was just an interesting problem in nuclear physical chemistry—an

unknown part of a whole systematics of the heavy elements. So I

started to look, and the work went quite well, and in about a year and

a half I had discovered uranium-233.

We used the Berkeley cyclotron—an accelerator machine—to develop

very high energy particles, and from this to develop neutrons with

which we could bombard natural thorium. By a complex series of

chemical steps I was able to isolate and prove the existence of

uranium-233 at a time when I had four one-millionths of a gram. This

was not an amount I ever saw—you traced it around by its alpha

particle radioactivity. So all the chemistry I was doing, I could

never see the material I was working with; I was only tracing it. I

had to measure the amount I had by its radioactivity—instead of a

scale that uses gravity, you’re using radioactivity to weigh things.

By then, things had shaped up to the point that it appeared

possible America would enter the war and that the discovery of nuclear

fission might mean that nuclear bombs were possible. Scientists in

this country voluntarily stopped talking about their work in public.

It was an informal agreement.

It was possible that uranium-233, which I had discovered, might be

one of the substances used to make a bomb. It depended on whether it

fissioned more easily or less easily than plutonium, which had been

discovered by Seaborg, or than uranium-235, which exists naturally.

These were the three candidates to make a bomb, and certain physics

measurements on the fissionability would determine which was the best.

So I started to work on trying to find out if uranium-233 was

fissionable, and I proved that it was, using what’s called both slow-

and fast- moving neutrons. In fact, I proved that it was even better

in many respects than plutonium for this purpose.[4] All that was

connected with my Ph.D. thesis which I finished in 1942.[5]

The Manhattan Project: Building the A-Bomb

I was all in favor of making a bomb. And I want you to know that I

have no guilt about it. I would do it again, and for this reason: as

I appraised the situation at that time, there was not for a long time

in history any worse aberration of human conduct and human monstrosity

than the Nazi regime in Germany. And the idea of an atomic bomb that

could win the war against Germany was highly attractive to me. While

nothing required me to work more than eight hours a day, I spent at

least sixteen in the average day on the bomb project. I was very

highly motivated simply because I thought it was important to win the

war against Germany.

By this time the Manhattan Project had started, and the government

was backing it. They hadn’t backed any of our work before. We were

working for peanuts in terms of money. Seaborg’s group became one of

the integral parts of the bomb project, and then Seaborg left to go to

Chicago to the headquarters where the Fermi reactor—the first one—had

run. They were definitely going to go ahead and attempt to make a

bomb out of plutonium.

I stayed behind in Berkeley and became the leader of the residual

Berkeley group that Seaborg had had before. Seaborg and a fellow by

the name of Arthur Wahl were the first two people in the world to work

with plutonium, and I became the third.

In order to make a bomb out of plutonium, we had to learn a hell of

a lot of chemistry of plutonium, at a time when practically no

plutonium was available. We had never even seen it. We were tracing

its radioactivity around by its alpha radioactivity.

But we learned quite a bit about the chemistry of plutonium in the

year that followed. About that time, J. Robert Oppenheimer[6] took a

large group down to form the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico,

which was to be a secret isolated lab, to go on with the bomb work.

The other labs—in Berkeley, Chicago, and Columbia—were feeders to

that project.

Very shortly thereafter, Oppenheimer came up to see me and said,

"We have a very desperate problem. We need to have half a milligram

of plutonium."

That was something like ten times what had ever been available

before.

"You’re going to have grams of it in a year," I said, "when the Oak

Ridge reactor runs. Why do you need half a milligram now when you’re

going to have two thousand times that in a year?"

"We need that measurement," Oppenheimer said. "We need it badly

because it will alter the whole way the Project goes."

"Well, what do you want?"

"Well," he said, "I talked to Ernest Lawrence"—who was head of the

Lawrence Laboratories—"and he has agreed to give up the cyclotron for

as long as it will take to have you make some plutonium. We figured

out," he said, "that you could make half a milligram if we bombarded a

ton of uranium for maybe a month or two."

So after a few hours of thinking about it I finally agreed to do

it, to place a ton of uranium nitrate—that’s two thousand pounds—and

then go through an intricate and complicated series of steps to purify

the plutonium from all that uranium. We were going to make half a

milligram, less than a needle in a haystack.

It was a big, dirty job, and dangerous, because uranium gets hot as

a firecracker with radioactivity from all the fission products that

accumulate—all the strontium-90 and all the cesium-137 and the

radio-iodine,

and everything else. I didn’t know enough to have good

sense, but I knew that it was dangerous.

To make a long story short, we bombarded the uranium night and day

for six or seven weeks. I set up a small factory and built it on the

Berkeley campus. In three weeks we isolated what turned out to be not

half a milligram, but 1.2 milligrams of plutonium. Pure. In about a

quarter of a teaspoon of liquid, out of this ton. I gave it to the

Los Alamos Lab.

So I was the first chemist in the world to isolate milligram

quantities of plutonium, and the third chemist in the world to work

with it. We knew nothing of its biological problems.

I got a good radiation dose in doing that work. I feel that since

that time, with each year that’s passed, I consider myself among the

lucky, because some of the people who worked closely with me in the

Lawrence Radiation Lab died quite prematurely of leukemia and cancer.

I’m still at a very high risk, compared to other people because of the

dose I got. I probably got a hundred, hundred and fifty rems in all

my work. That’s a lot of radiation. And damn stupid, but nobody was

thinking about biology and medicine at that point. We were thinking

of the war. So we did it.

For the next few years Gofman continued working to develop

processes for separating plutonium. "It was already clear that we

were going to have big reactors running at Hanford, Washington, to try

to make enough pounds of plutonium to make a bomb, and they’d need to

be able to separate it." The process Gofman had worked out in

Berkeley to separate one milligram of plutonium was a candidate

process. After working intensively on the project, Gofman decided in

1944 that he was no longer needed. "I felt that from here on out it

was strictly engineering work. We didn’t know if the war would last

one year or ten. I didn’t want to do engineering work—not that I was

against the bomb or anything—I just felt the project didn’t need my

kind of talent any more.

Gofman applied to the second-year class at the University of

California Medical School and was accepted in their accelerated

program. He was still a medical student when the bombs were dropped

on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. "When I heard the announcement of the

explosion of an atomic bomb, I knew they’d completed the project.

That was my only reaction." He finished medical school in 1946 and

did his internship in

internal medicine at the University of

California Hospital in San Francisco. Then in 1947 he was offered an

assistant professorship at the University of California, Berkeley,

which he accepted.

Gofman remained in that position, teaching and doing research from

1948 to about 1961. He made a number of major discoveries working

with cholesterol and lipoproteins.[7]

By 1954 he had moved up to a

full professorship and had become internationally known as a result of

numerous publications on coronary heart disease. Then something

happened which altered the course of things for him.

Early in the 1950s a controversial decision had been made to set up

a second weapons laboratory in the United

States.[8] The first

weapons laboratory was at Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the atomic

bomb had first been designed and tested. The second, the Lawrence

Livermore National Lab, was set up at Livermore, fifty miles east of

the University of California at Berkeley under the aegis of the

University’s Lawrence Radiation Laboratory, of which Gofman was a

member. Much of Gofman’s funding at the Lawrence Radiation Lab came

from the Atomic Energy Commission, although at the time Gofman was not

doing any radiation work himself. With the decision to set up a new

weapons laboratory, there were two parts to the Lawrence Lab—one at

Berkeley and one at Livermore.

Ernest Lawrence called me in one day. We were good personal

friends. "I’m worried about the guys out at Livermore," he said. "I

think they may do some things to harm themselves. You’re the only

person who knows the chemistry and the medicine and the lab structure.

Could you do me a favor and go out there a day or two a week and just

roam around and see what the hell they’re doing, and see that they do

it safely? If you don’t like anything they’re doing, you can tell

them that your word is my word, that either they change, or they can

leave the lab."

So I decided to do it.

While I was out there—to have something to do between times of

roaming around—I organized a Medical Department at the Livermore Lab.

It was then a lab of about fifteen hundred people. It’s now about

seven thousand. I organized the Medical Department and served as the

medical director. But I was there only a day or two a week. The rest

of the time I was in Berkeley teaching.

In the course of my wandering around I got to know all the

weaponeers who were working there. I worked with them, helped them

with some of their calculations on health effects and problems of

nuclear war, and so forth. They were making bombs, new bombs,

hydrogen bombs, designing all the bombs within the nuclear subs, for

missiles and so forth.

I stayed out there until, one day, in 1957, I thought, I’ve done

this long enough. Besides, one of my former students, Dr. Max Biggs,

had come back as assistant director of the Medical Department. It was

time for me to go back to Berkeley, to teach and also return to my

research. By about 1960 I decided that, although there was still a

lot left to do in heart disease, the excitement of my early

discoveries, the night and day work, wasn’t there any more. I’m not

very good at dotting I’s and crossing T’s. If it’s not something

really new and unknown, it’s not something I want to do.

By then, two of my students were on the faculty and were doing very

nice work. So I said, "I’m going to get out of the heart disease work

totally. You take over." They did, and they’re still there, doing

fine work. I shifted my major emphasis to the study of trace elements

in biology and worked hard on that from about 1959 to 1962.

In 1962 I got a call from John Foster, who was by then the director

of the Lawrence Livermore Lab.

He said, "I’d like to have you come out." I’d met with him and

worked with him during the years that I’d been at Livermore. He said,

"We had a very interesting approach from the Atomic Energy Commission.

They’re on the hot seat because of this 1960s series of tests which

clobbered the Utah milkshed[9] with radio-iodine. And they’ve been

getting a lot of flak. They think that maybe if we had a biology

group working with the weaponeers at Livermore, such things could be

averted

in some way—like you’d advise us not to do this or to do this

differently."

And I said, "So?"

He said, "They’re willing to set up something very nice—like a

biology and medicine lab at Livermore, with a very adequate budget,

starting at three to three and a half million dollars a year. You

know, we’ve got the best computer facilities in the country. We’ve

got engineering talent coming out of our ears, and electronic and

mechanical engineering. So you’d have support. What do you think of

coming out here and setting that up?"

"That’s crazy," I said. "I’m perfectly happy in Berkeley. I’ve

got my research. I’m up to my neck in my trace element research.

I’ve gone down from having to supervise fifty people in my heart

disease project to where I now have three people working with me. And

it’s just the way I like to work. I can be in the lab, and I don’t

have to think about administrative details. And now you’re telling me

to come out and head a division and be back in the administrative

field. I’ll be out of the lab—"

"Oh, no, no, you won’t be out of the lab. Just organize it. And

after a year or two you can get back in the lab full time, but under

circumstances that are much better than you’d ever have."

"Well, I can tell you one thing," I said. "I wouldn’t consider

giving up my professorship to take this thing, because I don’t trust

the Atomic Energy Commission."

He didn’t seem surprised at that.

I said, "I don’t think they really want to know the hazards of

radiation. I think it’s important to know, but I don’t think they

want to know."[10]

I kicked around the idea of going back to Livermore for a while.

Sometimes you have a lapse of cerebration, and in one of those weaker

moments I finally agreed that I would go to Livermore and do that job,

because Johnny Foster said, "Listen, the AEC can’t fight the

University

of California, the Regents, and this lab. And I can tell

you one thing, if they try to prevent you from telling the truth about

what you find about radiation, we’ll back you and the Regents will

back you, and they’ll just have to eat it."

Well, those were nice words. I didn’t completely believe them.

But the Regents wrote me. The president of the university wrote me a

letter of terms, stating that if for whatever reason I was unhappy

about the Livermore set-up, or the AEC’s behavior, I could return full

time to my teaching with no further explanation.

So I cut my teaching down to 10 percent, and took two posts at

Livermore—one as head of a new bio-medical division, the exact

mission of which was to calculate and do the experimentation needed to

evaluate the health effects of radiation and radionuclide release from

weapons testing, nuclear war, radioactivity in medicine, nuclear

power, etc.—all of the atomic energy programs. And I was given a

three million dollar budget to start. I pulled in ultimately about

thirty-five scientists—some who’d worked with me before at the

university, some from outside—and finally built up a division which

was one hundred and fifty people total, with engineers, technicians,

and so forth, including the thirty-five senior scientists. I also

became an associate director of the entire laboratory. There were

nine associate directors and a director. Anything in biology or

medicine was my general area. As an associate director, once a week I

was at directors’ meetings that concerned all lab matters. So I was

involved in the bomb testing and everything else.

A Visit to the Washington Office of the Atomic Energy Commission

A couple of disturbing things happened. Within a few weeks after

I’d gone out to Livermore, I had a call from an Atomic Energy

Commission official, who said, "You’ve got to come into Washington

next week."

"What for?"

"I can’t tell you over the telephone."

"Sure, I’ll come."

I got there. There were five other guys from AEC-supported labs

around the country assembled in a room, and this AEC official.

"The reason I called you together," he said, "is we have a problem.

We’ve got a man in the bio-medical division in the Washington AEC

office by the name of Dr. Harold Knapp who has made some calculations

of the true dose that the people of Utah got from the radio-iodine

from the bomb tests in 1962. And he says that the doses were

something like one hundred times higher than we’ve publicly

announced."

So this group of six people, of which I was one, said, "What do you

want us to do?"

"We must stop that publication," he said. "If we don’t stop that

publication, the credibility of the AEC will just disappear, because

it will be stated that we’ve been lying."[11]

I said, "Well, what can we do? What do you want us to do? If

Knapp has that evidence, then he ought to publish it."

"We can’t afford to have him publish that evidence," he said.

"But if it’s right, we can’t stop him. It’s not our job to stop

him."

He said, "Well, will you do this? Talk to him. Look at the data,

and see if you can convince him that it would be better not to publish

it."

So he brought Knapp in the room and he left. Knapp was surly, and

properly so. Because here was a guy that did a straightforward

scientific job, and he had this evidence, and he wanted to write it

up.

And he said to the group, "What’s wrong with what I’ve done?"

We hadn’t even seen his data yet.

He gave us his data and said, "Do you think I’m too high? Or do

you think I’m right? Or too low?"

We looked at the data, and as a matter of fact, there were a few

minor technical questions the people had to ask him, and then we

concluded that the guy had a very good scientific story and it ought

to be published. So we told Knapp he could leave, and the AEC person

came back in.

"Did you get anywhere?" he asked.

"Yeah," we said, "we think Knapp ought to publish his data and you

face the music."

He was very disappointed. But since the committee wasn’t going to

do anything—this is a matter of record now—do anything to help the

AEC try to suppress scientific truth, Knapp did publish. And the sky

didn’t fall. Unfortunately, in this society it takes a hell of a lot

more than revealing some awful things for the sky to fall.

But it taught me something that was very, very different from what

Glenn Seaborg had told me. (By now my former professor was chairman

of the Atomic Energy Commission.) When we had signed the contract for

the Livermore work, I told him, "You know, Glenn, you ought to think

twice about my being the head of this thing. Because I don’t really

give a damn about the AEC programs, and if our research shows that

certain things are hazardous, we’re going to say so. And so why don’t

you think twice about me taking this job?"

"Oh, Jack," he said, "all we want is the truth."

And here within a matter of a few weeks one of his chief men at the

AEC is asking us to help suppress the truth. So I came back to the

lab and I told Johnny Foster, "Well, the first encounter with

Washington was to help with a coverup."

And he said, "Well, how did you handle it?"

"We told them to go to hell."

He said, "That’s fine. That’s fine."

So there was no further flap from that. But it taught me something

about the Washington office—that they would lie, coverup, minimize

hazards. My worst suspicions were confirmed.

Plowshare: A Minor Disagreement[12]

There was a project called "Plowshare"—peaceful uses of nuclear

bombs. Big project. They wanted to dig a new Panama Canal with 315

megatons of hydrogen bombs. The current Panama Canal is not too good

for large ships, and they were thinking of digging a deeper canal.

They were going to implant hydrogen bombs and blow a big hole in the

ground. Two places were being considered—Panama and Colombia—and

negotiations were under way with those countries. They would place

more bombs and blow them up, and finally dig this whole trench with

bombs. But all the radioactivity would spew into the atmosphere and

over the countryside.

One of my first assignments was to figure the biological hazard of

that, and I concluded by 1965 that the project was biological

insanity. Just an awful thing for the biosphere. Kill a lot of

people from radiation, from cancer eventually. Project Plowshare.

Turning our swords into plowshares.

Even with the fragmentary knowledge we had then, I opposed the

project—which did not earn me a lot of favor with the Atomic Energy

Commission. They thought I was being obstructionist. But my

objections didn’t stop it at all.

What stopped it were U.S. efforts to negotiate a test-ban treaty.

And the ability to have a test-ban treaty with ongoing shots for

so-called peaceful nuclear explosives could always be shots that were

really for military purposes. So they elected to stop that project

temporarily. It was really nothing to do with the biological hazard

that made them quit. It was because of these political negotiations

to keep other countries who didn’t yet have bombs from developing

them. As though the ones that do have them can be trusted for

anything.

In any case, in 1965 the bio-medical division got known in the lab

as "the enemy within" because we opposed things like Plowshare. But

it was really fairly good-natured. In no way did it interfere with my

status in the lab. I did give up the headship of the department after

two and a half years. I appointed one of my junior associates as

chairman of the division so I could go back into the lab. I had a new

project by then, on cancer and chromosomes and radiation. It was an

area I was very interested in, and a new one for me.

Things went quietly until 1969.

Sternglass Challenges the AEC

By 1969 Johnny Foster had gone on to head the Defense Department

Research and Engineering, under McNamara, secretary of defense, and he

was no longer head of the lab.

That year a man by the name of Dr. Ernest Sternglass, who had been

studying infant mortality, published some papers saying that something

on the order of four hundred thousand children might have died from

radioactive fallout from the bomb testing. And "Esquire" published an

article called "The Death of all Children" based on Sternglass’s

work.[13]

The AEC was desperately worried about this because they were just

then trying to get the antiballistic missile through Congress, and

they thought if Sternglass’s work was accepted, it might kill the ABM

in the Senate. So they sent Sternglass’s paper to all the labs. I

got it, looked at it quickly, and wasn’t sure what to make of it.

But Arthur Tamplin, one of my colleagues, was much more into that

thing than I was. And I said to him, "Art, would you look at this?"

He came back about three weeks later and said, "I think Sternglass

is wrong. His interpretation of that curve is not right."[14]

I’ll say today—ten years later—the new evidence coming out

suggests to me that Sternglass may have been right. But Tamplin’s

argument seemed good to me at the time. I felt he should write it up

as a report. And he did, as an article to be published in the

"Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists," stating that he thought

Sternglass was wrong, and since people had raised the question, he

estimated how many deaths had been caused by fallout. His estimate

was four thousand, not four hundred thousand.

At Livermore, Tamplin became the "hero of the lab." He had

countered this man who was saying that something was going to hurt the

ABM program, which the lab was heavily involved in. So Tamplin was an

absolute hero, even to someone like Edward Teller, who all through

that period was also an associate director of the Livermore Lab.[15]

Tamplin wrote the paper and submitted it through the lab, to tell

Washington what he thought of the Sternglass thing.

I saw one of the top lab officials with whom I got along very well,

and he said, "Something’s wrong. I don’t know what’s going on, but

Washington AEC has called me up. They’re very disturbed about

Tamplin’s paper and don’t want him to publish it the way it is."

"Disturbed about Tamplin’s paper!" I said. "He’s the hero of

the day. He saved their neck on the ABM program. What in the world

can they be disturbed about?"

"Look, Jack," he said, "I don’t know what they’re disturbed about.

It’s not my area. Would you do me a favor and call this fellow at the

AEC?"

So I called the AEC and told Arthur Tamplin, "You better be on the

other line. Just in case. It’s your work they’re concerned about."

On the phone I said, "What’s on your mind about Tamplin’s study?"

"Oh," the AEC official said, "we like Tamplin’s study."

I said, "Gee, I heard you were terribly disturbed about Tamplin."

"No, no. We like Tamplin’s study. Very well."

"So what’s the problem?" I said.

"Well, Tamplin has proved that Sternglass is wrong, and that four

hundred thousand children did not die from the fallout. But he’s

decided to put in that paper that four thousand did die. And we think

that his refutation of Sternglass ought to be in one article—like the

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which is widely read—and that

his four thousand estimate ought to be in a much more sophisticated

journal."

"Well," I said, "I’ve talked to Arthur about this, and he says that

doesn’t make sense, because if you publish an article saying

Sternglass is wrong, the first thing anyone will ask you is what do

you think the right number is?"

"No, the two things are just separate," he said.

Arthur Tamplin was on the phone. I said, "Art, I don’t think it

makes sense."

"No, it doesn’t make sense to me."

I said, "What in the world is the sense in separating these two

things?"

And this AEC fellow said, "Well, one ought to be in a scientific

journal. "

I said, "What you’re fundamentally asking for is a whitewash. And

for my money, you can go to hell."

That’s where we ended the conversation.

So I saw my friend at the lab, and he said, "Did you call

Washington?"

And I said, "Yeah."

"What was it?"

"They wanted a whitewash of Tamplin’s four thousand number." I

explained it to him.

He said, "What did you tell them?"

"I told them to go to hell."

And he said, "Fine."

That was April 1969. And I never heard a word more about it.

Tamplin published that paper.

The Harassment Starts: Low-Level Radiation

During the 1950s and 1960s the, Atomic Energy Commission maintained

there was a "safe threshold" of radiation below which no health

effects could be detected. This so-called safe threshold provided the

justification for exposing American servicemen to atomic bomb tests,

for permitting workers in nuclear plants to receive a yearly dose of

radiation, and for operating nuclear power plants which released

radioactivity to the environment and exposed the general population

even during normal operation. But in the 1960s evidence began to come

in from around the world—from the atomic bomb survivors,[16] from some people in Britain who had received

medical radiation[17]—with

estimates of the numbers of cancers occurring per unit of radiation.

Gofman and Tamplin assembled these figures and concluded that there

was no evidence for the AEC’s so-called safe threshold of radiation.

In fact, they estimated that the cancer risk of radiation was roughly

twenty times as bad as the most pessimistic estimate previously made.

When Gofman was invited to be a featured speaker at the Institute

for Electrical, Electronic Engineers meeting (IEEE) in October 1969,

he and Tamplin decided to present a paper on the true effects of

radiation "So we gave this paper,[18] and said two things. One, there

would be twenty times as many cancers per unit of radiation as anyone

had predicted before, and two, we could find no evidence of a safe

amount of radiation—you should assume it’s proportional to dose all

the way up and down the dose scale." The paper did not attract much

public attention, only a small article in the "San Francisco

Chronicle" and nothing in the national press. Senator Muskie was

holding hearings on nuclear energy at

that time[19] and invited Gofman

to address the Senate Committee on Public Works. Muskie did not know

about the paper given before the IEEE but invited Gofman because of

his position as associate director of the Lawrence Livermore

Laboratory. Gofman gave an amplification of the paper he and Tamplin

had presented at the IEEE meeting entitled, "Federal Radiation

Guidelines Protection or Disaster?" This was picked up by the

Washington press.

Within two weeks I began to hear all kinds of nasty rumblings that

we were ridiculous, we were incompetent.

Here I’d been getting a budget of three to three and a half million

dollars a year for seven years, and suddenly I’m hearing rumors out of

Washington that my work is incompetent. That wasn’t a criticism of

me. That was a criticism of them. If they give someone three million

a year for seven years and in two weeks they suddenly decide he’s

incompetent, what’s wrong with them for seven years?

It was obviously related to what we’d said.

A guy from Newhouse News Service phoned me and said, "I have a

statement from a high official on the Atomic Energy Commission, and I

asked him about your cancer calculations, and he said that you don’t

care about cancer at all. All you’re trying to do is undermine the

national defense."

I said "Me, undermine the national defense?"

He said, "What do you have to say about that?"

"Nothing."

"You’re not going to deny it?"

I said, "Do you think I would lower myself to deny a statement like

that?"

He said, "You wouldn’t be considering a lawsuit for libel if I

publish that statement?"

"What I consider doing is my business," I said. "You’re a

journalist. You’ve got a story. If you’d like to publish that story,

you go ahead and you take your chances, but I’m not going to tell you

whether I have in mind a libel suit or anything else. You just do

what you want with it."

"You’re not going to deny the story?"

"No. I’m not even going to comment on something that low."

He never published the story.

The next thing we experienced was this. I’d had an invitation

about four months before, to come and give a talk in late December

’69. It was to be a symposium on nuclear power and all the questions

about it. And I’d said to the person inviting me, "You know, the

kinds of things you want from me are much better handled by Arthur

Tamplin, because that’s been the area he’s worked on. Instead of me,

could he give the talk?"

"Oh, that’s just fine," they said. "We wanted to be sure to have

one of your representatives there."

So he was scheduled to give the talk on December 28.

Well, this friend of mine at the lab asked to talk to me right

after the Muskie hearing. And he said, "Jack, I have a problem. The

AEC has contacted me, and they’re very disturbed about your IEEE talk

and your Muskie testimony."

"What are they disturbed about? I’ve sent them the paper, sent it

out to a hundred scientists. If they’re disturbed, they can tell me

what’s wrong with it."

"No, no. They’re not saying that," he said. "What they’re saying

is that it’s just embarrassing to them to have these things given at a

meeting and then in testimony before they’ve had a chance to review

it. If you would just in the future do me one favor, send them your

papers—your testimony—before you give it, I think the whole problem

would be solved. They just don’t want to be caught unawares."

"Well," I said, "that’s very reasonable. Sometimes we have a

scientific paper ready, sometimes we don’t, to give it to them three

weeks in advance or so. But we’ll try."

I talked to Arthur Tamplin. He said, "Sure, what do I care. They

can have it."

His paper was about a month from delivery before the American

Association for the Advancement of Science. So I said, "Would you

give me a copy of it for the lab to send to the AEC so they can scan

it?"

So he did. Three days later Tamplin came into my office mad as

hell, and threw this thing down on my desk.

Apparently someone in the lab had done some editing on it, and the

editing was such that all that was left was the prepositions and

conjunctions. All the meat was gone. This hadn’t even gone to

Washington. It was our own laboratory that had censored it! My own

colleagues who were going to protect us from censorship.

I went over to my friend and said, "What the hell is going on?

When you asked me if we’d give the papers to the AEC in advance, I

told you I wouldn’t tolerate any censorship. And you said, ‘Jack, do

you think I would tolerate any censorship?’"

He said, "Jack, be realistic."

"I’m very realistic," I said. "We’re just not going to tolerate

any form of censorship."

"You’re overwrought."

"Listen, you know what I’m going to do? I’m calling up the guy

from that meeting from the American Association. I’m going to tell

him what has been told to Tamplin—that if he gives the paper

unaltered, he cannot say he’s a member of the Livermore Lab, he must

pay his own travel expenses, and cannot use a lab secretary to type

the paper."

That’s what the lab had told him!

I said, "I’m going to call the AAAS[20] and tell them I’ll send a

letter instead of Tamplin going to the meeting. In the letter I’m

going to say that the Livermore Laboratory is a scientific whorehouse

and anything coming out of the Livermore Lab is not to be trusted."

"Jack, you’re just excited," he said. "Go home. Think it over.

Let’s talk tomorrow."

I said, "I’m really very cool, but if you want to talk about it

tomorrow, that’s okay. You know what I’m going to do."

The next day he came over to my office. "Well, did you get some

sleep and think it over?"

"Sure, I got some sleep, and I’ve thought it over. And I also took

care of what I told you I would."

He said, "What do you mean?"

"I called the guy from AAAS and told him what I was going to do,

that I was going to submit this letter to be read before the assembled

public meeting, that the Livermore Lab is a scientific whorehouse and

practices censorship."

He turned all colors and just stormed out of my office.

Well, the upshot was the lab backed off on virtually

everything—Tamplin could have lab funds and so forth. A couple of minor

modifications to the paper, which Tamplin agreed to and they removed

the censorship. So my statement was never read and Tamplin did go to

the meeting.

The Decision to Fight: January 1970

Gofman had resigned from his position as associate director of the

laboratory six months prior to this episode with Tamplin, although he

remained in the Livermore Laboratory as a research associate. "The

resignation of my associate directorship had nothing to do with

politics. I just thought it was time to go back to teaching."

Gofman was now teaching part-time at Berkeley and spending half of

his time at Livermore doing research. In January 197O he learned that

Tamplin had been stripped of twelve of his thirteen staff people.

I went back to my friend at the lab, and said, "You son of a bitch!

What you’re doing is so obviously just harassment to please the Atomic

Energy Commission. I didn’t think you could stoop this low."

"Jack, it’s not that," he said. "Tamplin didn’t want those

people."

"Don’t tell me Tamplin didn’t want those people. I know what

Tamplin wants. And he didn’t want to lose any of them. He’s got a

lot of work to do, and so do I on the radiation hazard question.

You’ve looked at our calculations. What the hell are you harassing

Tamplin for?"

"It’s not harassment," he said. "It’s just that the laboratory

budget was cut."

"The laboratory budget was cut 5 percent and Tamplin was cut 95

percent. That doesn’t make any sense."

But it stuck. I wasn’t able to undo it. I wrote a letter of

complaint to Glenn Seaborg, and he said, "I can’t interfere with lab

management." Which was bullshit too.

Then I started hearing that there were a lot of people from the

electric utility industry who were insulting us and our work. They

were saying

our cancer calculations from radiation were ridiculous,

that they were poorly based scientifically, that there was plenty of

evidence that we were wrong. Things like that. So I wondered what

was going on there. At that point—January 1970—I hadn’t said

anything about nuclear power itself. In fact, I hadn’t even thought

about it. It was stupid not to have thought about it. I just

wondered, Why is the electric utility industry attacking us?

I began to look at all the ads that I had just cursorily seen in

"Newsweek" and "Time" and "Life," two-page spreads from the utilities,

talking about their wonderful nuclear power program. And it was all

going to be done "safely," because they were never going to give

radiation above the safe threshold.

And I realized that the entire nuclear power program was based on a

fraud—namely, that there was a "safe" amount of radiation, a

permissible dose that wouldn’t hurt anybody. I talked to Art Tamplin.

"They have to destroy us, Art. Because they can’t live with our

argument that there’s no safe threshold."

He said, "Yeah, I gathered that."

"So," I said, "we have a couple of choices. We can back off, which

I’m not interested in doing and you’re not interested in doing, or we

can leave the lab and I go back to my professorship and you get a job

elsewhere, or we can fight them. My choice is to fight them."

He said, "I agree."

Congress Hears the Evidence

The system used to discredit scientists like us is usually to call

you before the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy—it’s a Congressional

committee—and they let you present your evidence, and then they get

all their lackey scientists, the ones who are heavily supported, to

come in and say why you’re wrong.

So I got the call just like I expected to from the Joint Committee.

Would I come in on January 18, 1970 to testify?

I said, "Art, just as expected, they’re ready to slice our throats

at a Congressional hearing. We’ve got a lot more evidence that’s sort

of undigested than we had when you gave your paper and we gave the one

at the Muskie hearings."

In about three weeks we wrote fourteen scientific papers. I’d

never done anything like that in my life. And we learned new things.

Stuff was falling together. We took on the radium workers. We took

some data on breast cancer. There was a whole study of radium workers

and their deaths. A guy at MIT had said they wouldn’t get cancer

below the safe threshold. We pointed out his papers were wrong.

There were the uranium miners, who were getting lung cancer. And we

analysed that and showed how it also supported the idea that there was

no safe dose. We studied the dog data. Studies were being done at

the Utah laboratory and sponsored by the AEC—they were irradiating

dogs and studying how many cancers appeared. We took a whole bunch of

new human and animal data and wrote fourteen additional papers that

buttressed our position, that indicated, as a matter of fact, that

we’d underestimated the hazard of radiation when we’d given the Muskie

testimony.

We were going to take all this as evidence before the Joint

Committee. But I wanted to be sure that our material got out to about

a hundred key scientists in the country in case the AEC tried to

prevent us access via the journals.

—That’s always something you have to worry about. The journals

can easily not publish what you want to say. It’s a simple technique.

If the journals have editors and staffs supported by an industry or

government agency, you can be blocked from getting your things

published.

So to be sure that people knew what we were saying, we sent our

material around to about a hundred separate scientists to let them

know what we were doing.

I went to the lab and said, "I want 400 copies Xeroxed." We had

put together 178 pages.

The dwarves who occupy such positions of course immediately ran to

the master and said, "Gofman wants 400 copies of this! Do we have to

do it?"

And so he came to me. "What’s this 400 copies of 178 pages?"

"Well, the chairman of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy has

requested that we testify. We need 200 copies to send them, and I

need 200 copies for other distribution. If you prefer, I’ll call up

Mr. Holifield, the chairman of the Joint Committee, and tell him the

laboratory even wants to censor things from Congress."

"Oh, no, no. Don’t do that!" he said. "We’ll do the papers. I

just wanted to know what you needed them for."

So we shipped off our 200 copies to the Joint Committee. Their

purpose was, of course, to distribute the papers to the people that

they were going to get to come in and attack us.

January 28 was the day. I presented the evidence based on these

fourteen additional papers.

At the end of the testimony, Mr. Holifield said, "Now I certainly

appreciate your presenting this material, Dr. Gofman. You realize

that with 178 pages of testimony we haven’t had all the time it would

take to digest it in detail, but we’ll invite you back sometime."

They didn’t have any answers. Their people were just caught

flat-footed, and meanwhile we’d gotten things out to a lot of people—a

much stronger story. Their little escapade failed.

One of the guys we had mailed the papers to called me up. He was

in the Public Health Service, in a division separate from AEC. It was

on a weekend.

"I’ve got something disturbing to tell you," he said, "but if I

tell you and you ever want to use it legally, I’ll deny that I told

you."

"That sounds like terribly useful information," I said. "I can’t

use it, but you think I ought to know it. Well, go ahead."

"Someone from the AEC came to my house last weekend," he said. "He

lives near me. And he said, ‘We need you to help destroy Gofman and

Tamplin.’ And I told him you’d sent me a copy of your paper, and I

didn’t necessarily agree with every number you’d put in, but I didn’t

have any major difficulties with it either. It looked like sound

science. And—you won’t believe this—but do you know what he said to

me? He said, ‘I don’t care whether Gofman and Tamplin are right or

not, scientifically. It’s necessary to destroy them. The reason is,’

he said, ‘by the time those people get the cancer and the leukemia,

you’ll be retired and I’ll be retired, so what the hell difference

does it make right now? We need our nuclear power program, and

unless we destroy Gofman and Tamplin, the nuclear power program is in

real hazard from what they say.’ And I told him no. I refused. I

just want you to know if you ever mention this, I’ll deny it. I’ll

deny that I ever told you this, and I’ll deny that he said it to me."

"Well," I said, "it’s nice to know. We realized that we were in a

war to the death, and that there was no honor, no honesty in the whole

thing, but that’s the way it is. You’re not going to stand behind

what you found out. That’s okay with me too."

Abolishing the Atomic Energy Commission

By now I was convinced that nuclear power was absurd and

fraudulent, that there was no safe level of radiation. Tamplin and I

were writing and giving talks against nuclear power. In June 1970 I

gave testimony at the Pennsylvania state legislature, recommending

that all new construction of nuclear power plants cease—at least for

five years—till the whole problem was sorted out. Our stock at the

Livermore Lab was zero.

But we couldn’t get them to fire us. They wouldn’t do that. If

they fired us, it would be an admission that they couldn’t tolerate

the truth. We put out more and more reports that were scientifically

damaging to the atomic energy program. Meanwhile our Muskie

testimony[21] had gotten very wide notice in the press, and Ralph

Nader had entered the action and was asking Muskie what he was going

to do about this testimony if it was so damaging to the nuclear power

program. Muskie contacted Robert Finch, secretary of HEW, and said,

"What are you going to do about this study of Gofman and Tamplin’s?"

So Finch went to the National Academy of Sciences and said, "I call

for a study of whether Gofman and Tamplin are right," and awarded the

National Academy three million dollars to do a study. Some sixty

scientists were invited to participate.

At no time did the National Academy of Sciences invite either

Tamplin or me to be on this committee or contact us—from 1970 to

today. But in 1972 the National Academy of Sciences published a

report called the BEIR Report—Biological Effects of Ionizing

Radiation—a long, thick report, in which they walked around the

problem as best they could, and finally concluded that we were too

high between four and ten times. But if you read the fine print, they

were admitting that we might just be right.[22]