I’m not saying there’s going to be a giant outbreak of methane. But I’m saying that that is a possibility that’s suggested by what’s been observed by the people who actually go out there and do measurements.

It came to me that there’s this huge disparity between people who think it’s the end of the world literally and figuratively because there’s a methane release that’s begun in the East Siberian Arctic region and that this is uncontrollable, it’s started, it’s ramping up.

And then there’s the huge majority of people wherever they are on the scale of understanding and acknowledging climate change is real and happening to activism—all of those people, there’s a lot of them who say, “Oh we can still pull out of this nosedive we’re in.”

And the thing that separates you into the one camp, the hair-pulling camp, and the “It’s okay,” the rather sanguine camp, is the Arctic methane and Is it coming out quickly and what are the prospects?

So I wanted to ask your experience about that and how you read other scientists. This is a video released by Yale Climate Connections. The particular animation we’re going to tune in on comes from the US Geological Survey, and it starts off with Carolyn Ruppel.

... methane all of a sudden. That is not a scientifically sound worry.

I don’t think we need to be afraid of any catastrophic methane release from the Arctic anytime soon. Certainly not in our lifetime.

If we mitigate or reduce human emissions, looks like you can avoid 70 to 80 percent of the permafrost climate feedback. That means that the the size of this ecosystem feedback to climate depends almost completely on what we do.

Stuart Scott:

Okay, I think that’s enough. Let me stop the share, They are responding to one woman who was freaking out over it and just had to get to the bottom of it. And so Yale is putting out this six-and-a-half minute missive saying “Don’t worry about it.” But I wanted to get your input on what is being stated here, what’s being implied.

PW:

Well, it’s staggering in a way. First of all, why did Yale feel the need to produce this? To hold together a bunch of scientists who were basically not basing their statement that nothing’s going to happen on science—scientific principles or on observations—but simply to say, ‘These things don’t happen and as a scientist I say they’re not going to happen.”

It’s a very surprising kind of unscientific denial by all of those people, and the fact that they all—that Yale felt the need to put something out that denied that something was going to happen is also extraordinary. You don’t do that, really unless you’re actually worried that it might happen and and you want to instill complacency.

Because you don’t—say some extremely unlikely event, like the Earth being hit by an asteroid. It is accepted that it might happen, it’s very unlikely of course, but could could happen. So the odds or the likelihood of it happening are known and we of course don’t have much of an idea what we would do if it did happen. But it’s not something that a university would feel the need to deny, to put out a statement with some distinguished astronomers denying that it will happen.

It’s that strange.

SS:

I didn’t start the video early enough perhaps, because the only evidence they give is from Carolyn Ruppel. Let me see if I can go back a few seconds in that video and cue it.

CR:And in fact, the thermodynamics helps you a lot on this because of the nature of the reaction; it’s an endothermic reaction. This is a problem when we try to produce methane from hydrates. It keeps shutting itself down, right? So it’s not a situation where we trigger breakdown and that that breakdown is going to suddenly—like the whole deposit is going to release its methane all of a sudden. That is not a scientifically sound worry.

SS:

So she says because the methane hydrates are endothermic they need heat. They absorb heat. Well, that’s what we’re talking about. The Arctic is heating up.

PW:

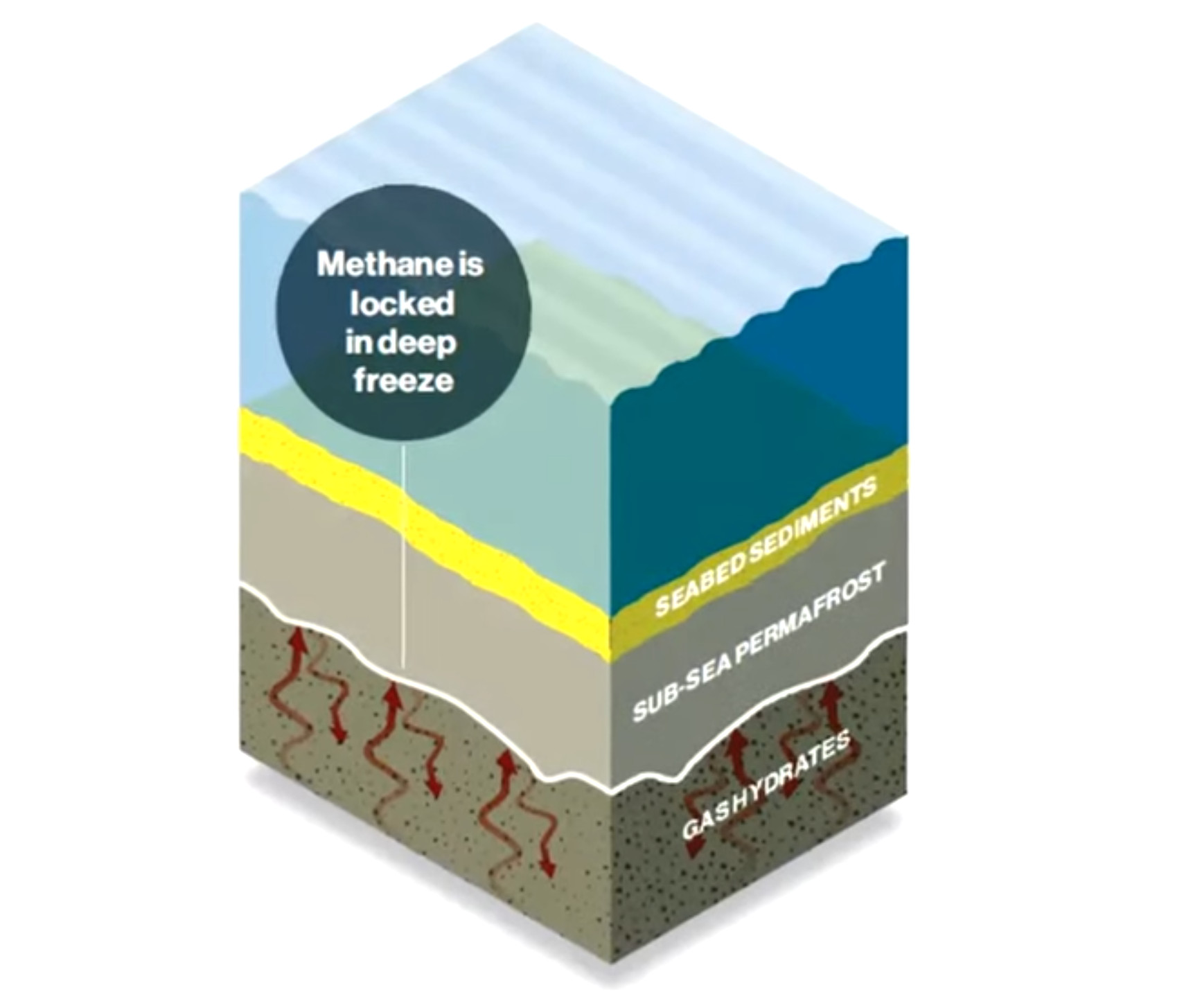

Yes—again, I don’t understand what she’s getting at. Yes, it’s an endothermic reaction and so methane hydrates turn itself into methane gas; absorbs heat. But I think the point about the danger here is that there is heat available and there’ll be a lot more heat available as the protective permafrost layer on the seabed thaws.

The first thing is, it’s like a pressure cooker. There’s a layer of a frozen ground. Basically, it’s like permafrost on land except it’s at the bottom of the sea, from when that area got flooded. And it’s there protecting the methane hydrates from actually coming out.

And it always has since the last ice age, but the situation’s changed completely. Instead of the seabed being at or near the freezing point, because the sea ice over the top of it, and that keeps the the coastal waters, the shelf waters, at or near the freezing point year-round. Instead we’re now got an increasingly long period in the summer—it’s up to about four months now—where the shelf waters are exposed to the atmosphere. There’s no sea ice there. And they warm up.

Arctic sea ice extent and thickness, Sep 2013-2016

I’ve measured 11 degrees in the Chukchi Sea, north of Bering Strait, which is the temperature of an English seaside resort in summer. The amount of warming up of this coastal waters is quite amazing. It’s it’s getting more and more each year. Once that heat gets—burns its way through or gets through the protective layer of permafrost, then the methane hydrates, although they need heat to turn them into methane, they’re going to have that heat, because that heat is then coming in from the warm shelf waters, which are now in touch with the methane hydrates because the permafrost layer has thawed.

So it’s a different situation than we’ve had before. It’s only been a situation for the last decade or so since serious retreat of the sea ice from coastal region of the Arctic happened. So it’s a different world and she should be looking at data that’s been obtained in that different world. And that’s really why these Russian groups like Shakhova—instead of ignoring the data and thinking and saying that something else is going on—it’s not a sort of stable, slowly varying thermodynamic situation now. It’s a new dynamics. And that’s what’s important. I’m not saying there’s going to be a giant outbreak of methane that will cause a huge increase in global temperatures. But I am saying that that is a possibility that’s suggested by what’s been observed by the people who actually go out there and do measurements. An increasingly small number of Arctic people actually do measurements in the Arctic.

SS:

An increasingly small number. A declining—

PW:

An increasingly small number of field scientists operate in the Arctic now. But you should pay attention to what they say because they’re the ones who do the measurements.

SS:

But Natalia Shakhova is not notoriously vocal, publicly. She doesn’t give very many interviews. So it’s very hard to know what their research has indicated recently. Have you had recent touch with her? Do you know what what the assessment is now of the heating and the methane outbreak?

PW:

Not very recent, no. I basically go on her published papers, and they have a large number of papers published in good journals, in Nature and Science, on what their observations demonstrate. And not only—they’re not demonstrating the potential outflow of methane from the Arctic; they’re demonstrating the real

SS:

—the actual—

PW:

methane from the seabed. There’s data from underwater vehicles showing methane plumes, and these are things that really would worry me. I’ve seen gas plumes coming up in the Arctic because of having worked on oil blowouts. This is the same thing. This is a seabed source, distributed over an area of maybe a kilometer or two, producing a large amount of bubble plumes where the methane is the bubbles and coming up to the surface and and being released into the atmosphere. And they’re there.

Whenever you go to the Arctic, to the East Siberian Sea—and now also to the Laptev Sea and the Kara Sea—you see these things. And it’s not just if you don’t want to believe the Russians for some reason. It’s also been done by the Swedes and Norwegians and other people involving expeditions on the Oden, which is a Swedish icebreaker. They see exactly the same thing.

So everybody who goes there sees this thing happening. Then the scientific question is: Will this process accelerate to the point where it’s giving out enough methane to cause a global climate impact or is it something that will remain at a fairly low level and something that you see when you’re up there but won’t necessarily accelerate out of hand?

That’s the question. But you have to base your thinking about that on the sum total of the observations. And they’re not just Shakhova. Although she’s done a huge amount of work[ResearchGate][Academia.edu]. But it’s also the people on the work from the Oden, and that’s the whole Swedish and Norwegian group.

So it’s very odd. I’ve noticed this kind of denial of methane seems to be that—well, no, why? I mean it’s not as if we’re talking about kinds of extraterrestrials or telepathy or some other field of science that’s forbidden to discuss or do anything with.

SS:

That’s physics.

PW:

It’s just methane. It’s stuff.

SS:

One of the things that I wanted to share again by video now, we’ll watch a little tiny bit of an interview with Natalia Shakhova. I want to start getting underneath this idea of why the worldview of scientists might affect their objectivity. So if I may, she’s discussing her attempt to get a paper published in Nature Geoscience. Let me see if I’m at the right point.

Natalia Shakhova:... our American colleagues. They reported about a few hundred plumes in the North Atlantic area. They didn’t measure even methane in the water column. They didn’t do anything. They just recorded the plumes like that. But they reported fluxes already, extrapolated to the area. And they never been beaten for that?

SS:

“And they’ve never been beaten for that?” In other words, that’s not sound. Okay, let’s go on.

NS:They’ve been published and they’re well done. We’re doing 10 years.

SS:

Now she’s talking about her work in the area.

NS:I’ve developed the method of direct measurements, in-situ calibration. Unprecedented. No one does—did that before. And we still, we do have the idea how we could extrapolate. We did come up with the ranges of the fluxes. But we still cannot do extrapolation, because everyone says, “What are you doing? How could you?”

SS:

So they doubt her extrapolation based upon actual field work, because it’s so high in comparison to the rather sanguine NASA, NOAA, American USGS. She says a couple of other things but she put her paper out there and the only comments that she got back were similar, like “You can’t publish this data. It must be wrong. Your data must be wrong.” Excuse me? I went there I measured.

[Apparently this paper was published in April 2019:by Natalia Shakhova, Igor Semiletov and Evgeny Chuvilin (local PDF)

Received: 4 April 2019 / Accepted: 3 June 2019 / Published: 5 June 2019

Abstract: This paper summarizes current understanding of the processes that determine the dynamics of the subsea permafrost-hydrate system existing in the largest, shallowest shelf in the Arctic Ocean; the East Siberian Arctic Shelf (ESAS). We review key environmental factors and mechanisms that determine formation, current dynamics, and thermal state of subsea permafrost, mechanisms of its destabilization, and rates of its thawing; a full section of this paper is devoted to this topic. Another important question regards the possible existence of permafrost-related hydrates at shallow ground depth and in the shallow shelf environment. We review the history of and earlier insights about the topic followed by an extensive review of experimental work to establish the physics of shallow Arctic hydrates. We also provide a principal (simplified) scheme explaining the normal and altered dynamics of the permafrost-hydrate system as glacial-interglacial climate epochs alternate. We also review specific features of methane releases determined by the current state of the subsea-permafrost system and possible future dynamics. This review presents methane results obtained in the ESAS during two periods: 1994-2000 and 2003-2017. A final section is devoted to discussing future work that is required to achieve an improved understanding of the subject.

Keywords: East Siberian Arctic Shelf; subsea permafrost; Arctic hydrates; shelf hydrates

Methane: The Arctic's hidden climate threat : Natalia Shakhova's latest paper (14:02)

So she is implying in that interview that scientists are defending turf. I wanted to get your view and maybe personal experience on a censorship within the scientific community. If you could take that question away.

PW:

Yes. It’s partly censorship and partly simple, I guess, lack of objectivity, which scientists don’t apply to other things, but they seem to some—to apply to methane. When the first measurements of methane under emissions from the seabed were done by a British scientist—I don’t know him—but he saw methane coming from the surface of Spitsbergen at a water depth of about 500 meters. In that distance methane dissolves. As it rises it gradually dissolves. And so the methane plumes that he was seeing started at the seabed and didn’t reach the surface. They disappeared on the way up. And that was a very nice paper because it showed these methane plumes coming from the seabed disappearing because the methane was dissolving.

But Natalia’s work when she’s—and Igor Semiletov—when they started working they were working in the East Siberian Sea, where the water depth is only about 60 meters. In 60 meters the methane comes out. The plumes that they observed and actually recorded on sonar and filmed on with underwater vehicles were there, coming up to the surface, the methane coming out.

So it’s a different world from the deepwater place and yet the person who did the deepwater work pooh-poohed everything that Shakhova’d done because he said you can’t get—methane dissolves on the way to the surface so that you can’t get any methane emissions. But ignoring the fact that the water depths were completely different.

So there was something where you’d think an elementary scientific principle would be understood. But it wasn’t. So you can’t quote measurements that you make in the deep water of the Atlantic—or even in the Bering Sea, which is similar to the seas north of Alaska—and say there can’t be methane emissions in the East Siberian Sea, because we’re not getting any in the Bering Sea or in the north Atlantic Ocean.

It’s an unscientific thing to say. It sounds as if they’re trying to demolish her paper on the grounds that it can’t happen because it hasn’t happened somewhere else that we’ve been. But that’s completely unscientific. I’m just still puzzled as to why methane should be a topic where rationality no longer seems to act.

SS:

I’m reminded of a another non-scientific metaphor in a tale.

Nasruddin is a famous fictional person in the Sufi, the metaphysical arm of Islam. Mullah Nasruddin is sometimes represented as a wise person and sometimes as a fool. He’s the wise fool. In this particular parable, friends come walking along the street and come upon Nasruddin looking on the ground outside of his house and they say—this is at night time—they say to him, ‘What are you looking for Mullah?” And he says, ‘I’m looking for the keys to my house before I go away for the evening. I have to lock my house. I can’t find the keys.’ And they say, ‘Oh, well, let us help you.’ And they’re looking for a while and they said to him, ‘Well, where did you lose them?’ And he said ‘In the house.’ And they look at him shocked and they say, ‘Why aren’t you looking in the house?’ And he says, ‘Because there’s no light in there.’

So why are they—these scientists—looking out under the streetlight for the the methane release when there’s none under the streetlight? I think we’re going to have to go to just descriptive terms of “probable” or “improbable” or “very probable”.

Where do you see the probability of a significant enough methane release within say the next five to ten years?

PW:

I don’t—I wouldn’t venture to say what the probability is of a catastrophic methane outbreak. But I wouldn’t put it as infinitesimally small, like I’d say it might be something like twenty or thirty percent.

It’s significant and it needs to be studied because when we do analysis of climate change risks, we should be doing risk analysis. In fact, there’s an increasing movement to say, ‘When you assess what’s happening, what are the nasty things that are going to be happening to the planet, what may be happening, we should be doing a risk analysis.’ Which means you look at a phenomenon, that may or may not happen, like a big methane release. You estimate what the probability is that it will happen based on all the data that you’ve got and modeling. And then you calculate what the cost would be if it did happen. Multiply the two together and that’s your risk.

I think it is the case that the world’s coming round to doing risk analysis on many aspects of climate change as opposed to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change approach, which is not quantitative in that way. But this is with the single exception of methane risk. Because that would seem to be a very clear risk and something that in fact was picked up on by one of the leaders in Britain of the climate change research saying: ‘Here we have an effect which, if it happened, would be very serious. We can more or less assess the probability it will happen. So we can do a risk analysis on that and that may be one of the biggest risks in climate that hasn’t been considered so far.’

That was then just squashed and hasn’t been done and hasn’t been funded and ... for some reason ... well, I think I can think of the reason. I think the reason is that if it did happen, it would be very, very serious. I mean it would be a step change in global temperatures of, well, we’ve done an estimate it might be 0.6 of a degree. And that’s only with a fraction of the methane in the sediments of the Siberian Sea coming out.

But if you had 0.6 of a degree—or more, it may be—then in one step I think people need to think what that would do. I mean we’re concerned about warming, global warming, and we bandy about figures like saying two degrees is the maximum we can allow by 2050 or preferably one and a half. What we might really get is four degrees by 2100. These are all assumed to be temperature changes which occur gradually—not that gradually, increasingly fast—but not catastrophically.

But if this two degrees for instance happened in one year, and suddenly, because of a vast release of methane, what would it do? We could understand two degrees over 30 years, and the world could gradually adapt or not adapt. But at least the change would be slow enough that we could change our habits, what we could do, what we can try and do about it.

But if it all happened suddenly in one year we would just be completely flummoxed. We wouldn’t have a clue what to do, and the effects would be as great as two degrees in 30 years. But they will be happening instantly. Nobody as far as I know has modeled what the impact of a large step change temperature in climate would be.

SS:

It can’t happen, you know.

PW:

Yes, it can’t happen. You don’t have to model it. Even if it’s not huge. But the finite probability that there will be a catastrophic methane release means that we have to do the research on what would be the consequences of such a rapid release.

But we’re not doing it. Nobody’s doing it. Because everybody’s so afraid of giving any sort of credence to the possibility of a big methane release that they don’t want to even look at what the consequences could / would be. And so that’s really very, very scientifically bad.

Remember there was a book some years ago about what will be the consequences of a nuclear war? [The Medical Consequences of Nuclear War (1982)] The new concept of a nuclear winter came out of that—that it could produce a complete loss of habitability of the planet because of nuclear winter.

clip of Ronald Reagan:A great many reputable scientists are telling us that such a war could just end up in no victory for anyone because we would wipe out the Earth as we know it.

PW:

But somebody went to the bother of working out what would happen if we had a nuclear war. It’s not just that everyone’s going to be killed by the explosions and the radiation and so on. But there’s this climatic effect as well. So they did that work and that hopefully made, it made the politicians of this world even less likely to fire off nuclear missiles.

But nobody’s doing that analysis for a methane catastrophe or large methane emission. And they should. It might might not be that bad. But it might be very serious indeed.

SS:

I keep wondering who the They is that decides—you may have mentioned it already and I missed noting it.

PW:

Well, who are they? The first line of defense against knowledge are scientists themselves and science funding agencies. For instance, Natalia was complaining that she couldn’t get a paper published. Now it’s probably a perfectly good paper. But it goes to referees and if all the referees are endowed with this thinking about methane it won’t get published. The funding agencies—and she’s had this problem with funding agencies as well—will support work—the actual measurements that have to be made, which cost money, to go out in ships and do this—they’re not willing to support field research.

I’ve had that problem with the proposals I’ve written with others—in fact large groups of scientists—to funding agencies that they simply find reasons why they can’t support it. It’s really difficult to get support to do that sort of work.

You would hope that it would be regarded as a high priority. But it’s regarded as something where the agency can find reasons to turn it down. So the science doesn’t get—the measurements which are vital — don’t get done because you can’t get the funding to go out there. If you’ve done the measurements and you’ve got the results you can’t get them published because of the referees—the biases of the referees.

So that’s quite powerful defenses against human knowledge, which are set by science and science administrators. So you break through that first. Then you have the problem of what do we do as a world or as a as a system that’s confronted with the risk like that that maybe needs some precautions being taken.

SS:

Human folly even in the scientific community.

Sign & Share the

World Scientists’

Warning to Humanity

ScientistsWarning.org

Thank you for watching and sharing.

Questions & comments to

Contact@ScientistsWarning.org

© Copyright 2019, Stuart Scott

May be used freely for non-commercial purposes, providing that attribution is made by link to ScientistsWarning.TV