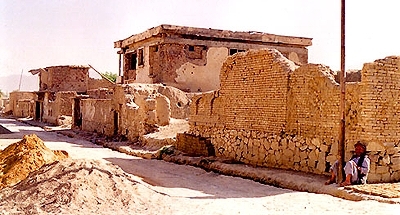

After 24 years of war, much of Kabul lies in ruins.Photo by Paul Wolf, June 2003

Date: Sun, 03 Aug 2003 21:46:25 -0400

From: Paul Wolf <paulwolf@icdc.com>

Subject: Unreconstructed Afghanistan

- U.S. Ambassador Confirms `Accelerated Effort' In Afghanistan (8/2/03)

- US to relaunch rebuilding of Afghanistan (7/27/03)

- Now we pay the warlords to tyrannise the Afghan people (7/31/03)

- We promised to wipe out the Afghan poppy fields.

Instead more heroin than ever is about to hit Britain (8/2/03)

- Report documents violence and repression by US-backed warlords (8/2/03)

- Bush Sells Out His Friends Again -- Why the US needs the Taliban (6/30/03)

- Unreconstructed (6/1/03)

U.S. Ambassador Confirms `Accelerated Effort' In Afghanistan;

Taylor Discusses Greater U.S. Role in Afghan Government on NPR

8/2/03 7:30:00 PM

To: National Desk, Media Reporter

Contact: Jenny Lawhorn of National Public Radio, 202-744-2802,

e-mail: jlawhorn@npr.orgWASHINGTON, Aug. 2 /U.S. Newswire/ -- NPR News has learned that the U.S. is retooling its policy toward Afghanistan, reportedly sending senior U.S. advisors straight into Afghan ministries. Ambassador William B. Taylor, the newly appointed U.S. coordinator for Afghanistan, confirmed advisors could be sent to work in Afghan government ministries in an "accelerated effort" to rebuild the country. He discussed these plans with NPR's Jacki Lyden in a report broadcast August 2 on NPR's All Things Considered.

"Part of this acceleration will include helping the government of Afghanistan take advantage of the international assistance that is coming in," said Taylor. "One of the things we are considering is to provide senior level advisors that can work with the government of Afghanistan in each of the ministries, both at a senior level and a the technical level, to help develop the capacities to provide services. So in the health ministry to provide healthcare services; similarly in the ministry of education to work with that minister to help build schools and train teachers. So, yes, part of what we are thinking about is both people and, again, resources."

NPR's Jacki Lyden asked Taylor whether there was a sense that U.S. efforts thus far have been incomplete, that matters in Afghanistan stand half-finished, that the Taliban is again resurgent, and that there is a danger of things getting out of control.

"I think there is the sense that a reinvigorated policy and reinvigorated effort on the part of the United States as well as the international community-again it's not just the United States, we are going to see our allies can join us in this acceleration-but there is the sense that this time is a good time to refocus attention," said Taylor. "There will be decisions and announcements made over the next several weeks."

Barnett Rubin, an Afghanistan expert and professor at New York University, who is currently in Kabul, said reports of a new U.S. aid package and a U.S. policy shift are gradually leaking out in the Afghan capital. "Apparently as part of this increase in aid, they are going to send out 15 ambassador-level advisors and 200 to 250 advisors to the Afghan government," said Rubin. "They are calling it here the `Bremerization' of Afghanistan," he said, referring to the U.S. civilian administration in Iraq. Rubin said this could create "a kind of colonial administration here in Afghanistan, which will not be effective, which will be resented a great deal and undermine attempts to build up the Afghan institutions."

Copyright © 2003 U.S. Newswire

US to relaunch rebuilding of Afghanistan

By Victoria Burnett, The Financial Times, July 27 2003 21:11The US is preparing to reshuffle top officials with responsibility for Afghanistan, expand the number of staff serving in the country, and award an additional $1bn (?870m, ?620m) in assistance in a bid to re-energise its reconstruction effort, according to US and Afghan officials familiar with the plans.

The policy shift, whose motto is "Accelerate Success", was a response by US State and Defense Department officials to a chorus of concern about the Afghan reconstruction process, officials said.

The US government was eager to point to Afghanistan as a success story as it faced difficulty in getting the situation in Iraq under control, officials said. It was also anxious that Hamid Karzai, the moderate, US-backed Afghan president, should notch up more achievements before elections, due in June 2004.

The assistance package, which could be announced this week, would include about $1bn in new money from Washington. US officials hope European allies will add about $600m. The total would more than double the amount of international assistance due to be spent in Afghanistan in the coming year.

An Afghan official said it was keen that the money should go to projects that would strengthen the local government.

"We're facing a very important year," an official close to Mr Karzai said.

"Will it go to the Afghan budget or through the [aid] agencies? That is the question."

But Afghan officials said there had been no talk of expanding peacekeeping operations, which are currently confined to Kabul.

The US intended to expand the number of officials posted to Afghanistan, adding groups of advisers to several key ministries, officials said. It was not clear how many people this would involve, although officials' estimates ranged from 70 to hundreds.

As part of the effort, the US will reshuffle some of its top Afghan officials. Robert Finn, ambassador to Kabul since March 2002, will leave in the next few days. Zalmay Khalilzad, currently US special envoy to Afghanistan, is widely expected to replace him, though this was not "110 per cent sure", a source close to the US embassy said.

Mr Finn, who is well liked and respected in Kabul, is expected to return to Princeton University, where he taught Turkic studies before his Afghan posting.

Robert Blackwill, outgoing US ambassador to New Delhi, is to become President George W. Bush's senior adviser on Iraq, Afghanistan and Iran at the National Security Council in Washington.

Mr Blackwill made a little-advertised visit to Kabul last week to "check things out", a source close to the embassy said.

Meanwhile, William Taylor, the US special representative for assistance to Afghanistan, is expected to take over from David Johnson as Afghan co-ordinator, the State Department position that oversees Afghan policy. Edward Luce in New Delhi adds: Pakistan will face "consequences" if it fails to honour its promise to stop cross-border terrorism into India, Mr Blackwill said on Sunday.

He said terrorists continued to move into India from Pakistan across the Line of Control that divides the disputed province of Kashmir.

This was in spite of the promise last year by General Pervez Musharraf, Pakistan's military ruler, to put a halt to terrorist infiltration.

"Of course, there are consequences if promises made to the US president are not fulfilled -- we are working hard to make this point," Mr Blackwill said. "Promises made to the president of the US ought to be kept."

Copyright © 2003 The Financial Times

Now we pay the warlords to tyrannise the Afghan people

The Taliban fell but -- thanks to coalition policy -- things did not get better

By Isabel Hilton, The Guardian, July 31, 2003Diehard defenders of military intervention in Iraq argue that it's too soon to carp, that time is required to restore order and prosperity to a country ravaged by every type of misfortune. Time, certainly, is needed, but is time enough? If the example of Afghanistan is anything to go by, time makes things worse rather than better. More than 18 months after the collapse of the Taliban regime, there is a remarkable consensus among aid workers, NGOs and UN officials that the situation is deteriorating.

There is a further point of consensus: that the deterioration is a direct consequence of "coalition" policy. Some 60 aid agencies have issued a joint statement pleading with the international community to deploy forces across Afghanistan to bring some order. While waiting for the elusive international cavalry, they have been forced to reduce operations in the north, where the warlords fight each other, and in the south, where the "coalition" forces try to fight the Taliban. Privately, many aid workers fear that it is too late. Even if the political will existed, foreign troops may no longer be in a position to restore order. To do so would require going to war with the warlords themselves.

The warlords, of course, as friends of the "coalition", are also part of the government. They have private armies, raise private funds, pursue private interests and control private treasuries. None of these do they wish to give up. All of them threaten the long-term future of Afghanistan, the short-term prospects of holding elections, the immediate possibilities of reconstruction and the threadbare credibility of Hamid Karzai's government.

It is not Karzai's fault. He is a prisoner within his own government: a respected, liberal Pashtun who nominally heads a government in which former Northern Alliance commanders -- and figures like the Tajik defence minister Mohammed Fahim -- hold the real power.

In the country that is fantasy Afghanistan -- or the Afghanistan of western promise -- a national army is being created which represents all ethnic groups, and elections next year will produce a representative, democratic government. In real Afghanistan, Fahim does not want to admit other ethnic groups to his army, which could create the conditions for a future civil war.

The new national army is supposed to be 70,000-strong. Last year, only 4,000 men were trained. The new recruits were vetted for Taliban connections and drug trafficking, but not for past human rights abuses. The defence ministry is a Tajik fiefdom; arms and cash, including British taxpayers' money, continue to be funnelled to the warlords; and senior UN officials have publicly doubted whether the elections will happen at all.

The funds offered to Afghanistan for reconstruction have been slow to arrive and less than promised, but aid agencies argue that the most urgent problems are not primarily a question of money. The bad news is that they are, therefore, not problems money will solve. What is needed is a fundamental change in the power structure. But this continues to be supported, on grounds of security, by both the British and the US governments.

There is money in Afghanistan, but it is in the wrong hands. Local warlords control local roads and exact crippling tolls that impede trade. Karzai is not able to exact the remittance of this money to Kabul.The government therefore, depends on funds from outside, part of which it uses, in turn, to buy off the warlords. At no stage of this dismal process do funds trickle down to the people of Afghanistan. The only dependable source of revenue for many returned farmers is the opium poppy.

Two million refugees have returned to Afghanistan, encouraged by the UNHCR and their weary host countries. For many this has been a tale of woe. There are few jobs; poverty and hunger continue.

Development and reconstruction experts agree that postwar reconstruction should begin with security and include the early encouragement of labour-intensive infrastructure projects which help the country and put wages into the pockets of those who need them. But this has not been applied in Afghanistan. Security never came because, when the Taliban fell, the US would not agree to the deployment of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) outside Kabul. Why? Because the US defence secretary, Donald Rumsfeld, was already planning the invasion of Iraq and did not want men tied down in peacekeeping.

The Pentagon prefers to pay the warlords to run the country outside Kabul, dressing up the exercise with a loya jirga in which 80% of those "elected" were warlords. Washington sources report that when Karzai appealed to Rumsfeld for support to confront one of the most notorious warlords, Rumsfeld declined to give it. The result has been that reconstruction is crippled, political progress is non-existent and human rights abuses are piling up.

Even straightforward reconstruction projects fail to bring maximum benefit to the Afghan people. To give only one example: road repair could be an opportunity to spend money usefully and to provide employment. But on the key road from Kandahar to Iran, which had not been repaired for 30 years, the central government failed to gain the cooperation of local powers. The stalemate was resolved when the repair contract was awarded to a US firm that brought in heavy machinery instead of using local labour.

What progress there has been is now threatened. The proportion of girls in school -- never more than half -- has begun to decline again: girls' schools have been attacked, and girls threatened and harassed on their way to classes.

A Human Rights Watch report published on Tuesday documents crimes of kidnapping, rape, intimidation, robbery, extortion and murder, committed not in spite of the government but by its forces -- by the warlords and their police and soldiers, who are paid, directly and indirectly, by US and British taxpayers.

The British have been shipping cash to Hazrat Ali, the head of Afghanistan's eastern military command and the warlord of Nangahar, who worked with the US at Tora Bora. His men specialise in arresting people on the pretext that they are Taliban supporters and torturing them until their families pay up.

If paying warlords had been an emergency measure, there would be room to hope that it would no longer be necessary once elections were held and a legitimate government in place. But this is a policy the consequence of which is that there is unlikely to be long-term peace or a democratic government.

The promised election date is less than a year away. The choice is to allow these local tyrannies to be painted over by a voting exercise conducted for propaganda purposes, or to challenge the warlords. Is Nato, which takes over ISAF in August, really prepared to do so? Somehow I doubt it.

Copyright © 2003 The Guardian

We promised to wipe out the Afghan poppy fields.

Instead more heroin than ever is about to hit Britain

From Nick Meo, The Mirror, August 2, 2003BRITAIN has abandoned plans to wipe out Afghanistan's poppy fields despite fears this year's opium harvest will be the biggest ever.

Now customs and police are bracing themselves for the arrival in the next few months of a glut of cheap heroin from the war- ravaged country, source of 90 per cent of the Class A drug on our streets.

Two months after the September 11 atrocities which led to the attack on Afghanistan and the fall of its cruel Taliban regime, Tony Blair pledged Britain would take the lead role in wiping out the lethal Afghan opium trade.

He said: "In helping with the reconstruction of Afghanistan we shall make clear we want it to develop farming of proper agricultural produce, not produce for the drugs trade."

The reality is a scandal. While the US spends an estimated £600million a month on military operations in Afghanistan, Britain has pledged just £70million over three years to build up an anti-drugs force.

None of the money has yet arrived. Meanwhile opium production since the fall of the Taliban, which banned the drug, has risen by some 1,400 per cent.

Last year production rose to 3,400 tonnes -- three quarters of the world total. Output is expected to increase. No major drugs arrest has been made.

Mirwais Yasimi, head of Kabul's Counter Narcotics Directorate, said: "I was expecting Mr Blair to do more.

"We need funds and assistance. This is not a job that can be done by the Kabul government alone.

"My men are dedicated. But they have received only tens of thousands of dollars from the UK, not even hundreds of thousands. Compare that to the spending on the war on terror."

Production is booming because poverty stricken Afghans can earn 15 times more from growing poppies -- which are chemically converted to heroin -- than farming wheat.

Tragically, the weak government in Kabul is powerless to stop the warlords behind the hugely profitable trade.

At first, it was thought wiping out the poppy fields would solve the problem. Each hectare of poppies produces about 35kgs of raw opium worth up to £900.

Last year Britain paid up to £800 per hectare compensation to farmers if they eradicated the poppy. But the scheme barely affected output. Now it has been dropped. British officials claim the policy was shelved in favour of building a force to tackle drug crime.

But though Mr Yasimi praised 50 customs experts who have helped train Afghans in drug detection, the squad has failed to yield major results.

He said: "Arrests are rare. They have just been small fry. Without resources my men can't do much. But the dealers get more sophisticated."

In the poppy centre of Jalalabad engineer Abdul Ghoss, one of Mr Yasimi's 20 men in the area, said: "We have no cars, no petrol, no radio, no phones and no computers.

"We heard the British government is involved in stopping the drug trade. Some British police came here and last week a British foreign minister, Bill Ramell, visited. They've promised us help but we haven't had any so far.

"My men want to stop opium. But what can we do against warlords with their private armies?"

Abdul Wahab, a pro-government commander, added: "We've destroyed some opium factories. But the people here are poor and need the money. We haven't had any help from the British."

A Western diplomat in Kabul close to the anti-drugs war, said: "It will take years to end this problem. We just have to keep nibbling away."

So as the politicians spout rhetoric and officials struggle with woeful resources, the fields of white and purple opium poppies continue to spread.

And on the streets of Britain yet more lives are wrecked and ended by the unstoppable scourge of heroin.

Copyright © 2003 The Mirror

Report documents violence and repression by US-backed warlords

By James Conachy, Human Rights Watch press release, 2 August 2003The 102-page report on Afghanistan issued by the New York-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) on July 29 catalogs the systematic violation of human rights by the militias of the Northern Alliance who were placed in power following the US invasion in late 2001.

The summary declares: "Much of what we describe may at first glance be seen as little more than criminal behavior. But this is a report about human rights violations, as the abuses described were ordered, committed or condoned by government personnel in Afghanistan -- soldiers, police, military and intelligence officials, and government ministers. Worse, these violations have been carried out by people who would not have come to power without the intervention and support of the international community. And these violations are taking place not just in the hinterlands of Afghanistan. The cases described here took place in the areas near the capital, Kabul, and even within Kabul itself...

"The situation today -- widespread insecurity and human rights abuse -- was not inevitable, nor was it the result of natural or unstoppable social or political forces in Afghanistan. It is, in large part, the result of decisions, acts, and omissions of the United States government, the government of other coalition members and parts of the transitional Afghan government itself. The warlords themselves, of course, are ultimately to blame. They have ordered, committed or permitted the abuses documented in this report. But the United States in particular bears much responsibility for the actions of those they have propelled to power, for failing to take steps against other abusive leaders and for impeding attempts to force them to step aside."

All the abuses recorded by the report took place in 12 provinces of southeastern Afghanistan -- home to one third of the population, including the 3 million people now crowded in Kabul. The warlords in control of this region are those most closely associated with the US.

In Kabul, the majority of soldiers, police and militiamen are loyal to the ethnic Tajik movement Jamiat-e Islami, or to Ittihad-e Islami, a Pashtun militia that has been aligned with Jamiat for over a decade. Jamiat-e Islami was one of the main militias of the Northern Alliance that fought alongside American troops during the overthrow of the Taliban and seized Kabul with US assistance.

With tacit US support, Jamiat-e Islami intimidated the loya jirga or grand council in June 2002 to award its leaders the major political posts in the "interim government." Human Rights Watch denounces the loya jirga for entrenching "the dominance of military leaders both at the local level and in Kabul." It comments that President Hamid Karzai has "little capacity to enforce his orders without the support of powerful military figures or the United States" and "barely retains control over Kabul-based security and military forces." HRW indicts the Bush administration for this state of affairs, noting that US military forces "cooperate with (and strengthen) commanders in areas within and outside of Kabul."

The Defense Ministry and control of the official armed forces is held by Jamiat-e Islami leader Mohammed Qasim Fahim, Younis Qanooni holds the Education Ministry and Abdullah Abdhullah holds the Foreign Ministry. Members of the organization command both the Kabul police and the national intelligence agency. Abdul Rabb al-Rasul Sayyaf, the leader of Ittihad-e Islami, maintains militia forces and exerts de facto control over the area to the west of the capital, including the city of Paghman.

Hazrat Ali, another warlord who has worked closely with the US military in post-invasion operations along the Pakistani border, exerts control over the city of Jalalabad to the east of Kabul, as well as the surrounding provinces of Laghman and Nangarhar.

HRW accuses these and other US-sponsored militias in Afghanistan?s southeast of presiding over "a climate of fear." The interviews and testimony conducted by HRW suggest an atmosphere of unchecked violence, theft, intimidation and sexual abuse of the population by the militias. This takes place in front of US and NATO troops in Afghanistan, who are a main military and political prop for the Northern Alliance?s despotism over the Afghan people.

The report documents cases of arbitrary arrests in which people are seized and held until their families pay a ransom. In Kabul province, a former delegate to the loya jirga told HRW that "there are arbitrary arrests all the time -- people held by the authorities for money." According to HRW, the various militias enforce mafia-style protection and extortion rackets in the areas they rule. Vehicles are regularly stopped at checkpoints and forced to pay either money or in goods to pass through. A shopkeeper in Kabul testified that Interior Ministry police collected protection money from him "every Thursday at around 3:00 p.m." Another told HRW: "If you do not pay, they close your shop and lock it with their lock. If you break it open, they will arrest you and put you in jail."

HRW claims it has "documented numerous robberies and home invasions by soldiers and police in many provinces of southeastern Afghanistan." In testimony cited in the report, police in West Kabul followed a trail of footprints from a robbed home to a barracks of militiamen loyal to Sayyaf, at which point they "got scared and turned back." In two cases cited by HRW, troops believed to be on Sayyaf?s payroll forced homeowners to tell where their money was by stabbing them with bayonets. An interviewee refers to militiamen looking at women with "bad eyes" and trying to "touch them." The report also cites witnesses alleging young women and boys have been raped in their homes or kidnapped off the street and sexually assaulted.

The report outlines the systematic political intimidation of the few political and media figures who have dared raise public criticism of the "interim government." A politician and publisher referred to as "H. Rahman" told HRW he was personally threatened by Younis Qanooni in November 2002 that he would "have no right to live any longer" if he continued to criticize the government in his newspaper. Members of the national intelligence agency visited his house and told him if he would be exiled, imprisoned or assassinated if he did not "change his policy." He received further threats on his life from Sayyaf and was beaten by soldiers in May 2003.

Another oppositional politician told HRW: "If a member of our party -- and any political party except the jihadis [a term used to describe the Northern Alliance] -- does anything publicly, he might be killed."

Other examples of political violence in the HRW report include:

- death threats, assaults and other intimidation by officials in and around Jalalabad against people speaking publicly in favor of educating girls or advocating women?s rights;

- the beating and imprisonment of two students who protested against nepotism at Kabul University by the chief of the Kabul police and Jamiat-e Islami member Basir Salangi;

- death threats and police intimidation against journalists and cartoonists who have been critical of Jamait-e Islami leaders.

In the lead-up to the invasion of Afghanistan, a great deal was written about the reactionary social policies of the Taliban, particularly its treatment of women. The HRW report charges that little has changed since the installation of the pro-US regime.

The presence of armed men who feel they are a law unto themselves and often use religious dogma to terrorize the population has created such anxiety that many women, and especially teenage girls, are prevented from leaving their homes except when accompanied by family males. The fear is such that in some areas families will not even take pregnant women to the hospital.

While some girls are now attending school, real or perceived security concerns in many areas cause families to pull their daughters out of education as they reach puberty. A UNICEF spokesman estimated for HRW on May 8, 2003 that no more than 32 percent of girls were attending school and in some areas the participation rate was only 3 to 10 percent. A Jalalabad journalist told HRW that only 10 girls were attending the city?s university. Male teachers in Kabul have been beaten by police for teaching girls. The full body burqa is still worn by most women outside of Kabul due to fear of fundamentalist attacks on either their male companions or on the women themselves.

The HRW report comments: "In discussions on women?s rights in Afghanistan, it is often heard that restrictions on women?s and older girls? liberty of movement, access to education, political participation and privacy, including the right to choose whether to wear a burqa, are cultural, or that they are part of Afghan tribal codes or religious traditions. But when soldiers and police abduct and rape women and girls with impunity, and where these actions have the effect of denying them access to education, health care, jobs and political participation, women and girls are not experiencing ?culture.? They are experiencing human rights violations."

The Human Rights Watch report is available in both html and PDF formats at: http://www.hrw.org/reports/2003/afghanistan0703/.

One can safely assume that the HRW report provides only a pale indication of the social devastation and political chaos that reign in Afghanistan nearly two years after the American invasion. The reality on the ground in the Central Asian country completely exposes the lies that were used to justify the US intervention, whose essential aim was to replace one set of warlords with another that would be more pliable to American interests, above all its designs on the rich oil and natural gas resources in the adjoining Caspian basin.

Note: a few months before the September 11, 2001 attacks, HRW produced an excellent analysis of the arms trade in Afghanistan. Interestingly, Massood's United Front (renamed the Northern Alliance by others) was being supported by Iran and Russia, while the Taliban were organized and funded by Pakistan -- America's old ally. Massood's September 9, 2001 assassination paved the way for the US to co-opt his organization and use them to oust the Taliban. These "commanders" now rule most of Afghanistan, and are generally referred to as "warlords". -- Paul

Afghanistan: Crisis of Impunity

The Role of Pakistan, Russia, and Iran in Fueling the Civil War

http://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/afghan2/Pakistan's Support of the Taliban

http://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/afghan2/Afghan0701-02.htm#P350_92934Foreign Assistance to the United Front

http://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/afghan2/Afghan0701-03.htm#P491_143097

Bush Sells Out His Friends Again -- Why the US needs the Taliban

By Ramtanu Maitra, The Asia Times, circa June 30 2003Since Pakistani President General Pervez Musharraf made his much-acclaimed visit to Camp David and met US President George W Bush on June 24, new elements have begun to emerge in the Afghan theater. US troops in Afghanistan are now encountering more enemy attacks than ever before, and clashes between Pakistani and Afghan troops along the tribal borders have been reported regularly.

On July 16, speaking to Electronic Telegraph of the United Kingdom, US troop commander General Frank "Buster" Hagenbeck, based at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan, reported increased attacks over recent weeks on US and Afghan forces by the Taliban, al-Qaeda and other anti-US groups that have joined hands. He also revealed some other very interesting information: the Taliban and its allies have regrouped in Pakistan and are recruiting fighters from religious schools in Quetta in a campaign funded by drug trafficking. Hagenbeck also said that these enemies of US and Afghan forces have been joined by Al-Qaeda commanders who are establishing new cells and sponsoring the attempted capture of American troops. One other piece of news of import from Hagenbeck is that the Taliban have seized whole swathes of the country.

Reliable intelligence

Hagenbeck's statements were virtually ignored in Washington. Also ignored were a number of similar statements issued from Kabul by Afghan President Hamid Karzai and his cabinet colleagues. On July 17, presidential spokesman Jawed Ludin spoke to the Pakistani newspaper The News of the Afghan government's concern over the volatile situation on its border with Pakistan. Ludin urged Pakistan to "take steps" to prevent the Taliban fighters from crossing over to launch terrorist attacks against Kabul. "We will take it seriously to confront it," he warned. "So our expectation is for all those involved in the war against terror to take serious steps," Ludin added, clearly addressing the Bush administration.

A week later, on July 24, in an article for The Nation, a Pakistani news daily, Ahmed Rashid, the well known expert on the Taliban and Afghanistan, quoted President Hamid Karzai, during an interview at Kabul, as saying: "As much as we want good relations with Pakistan and other neighbors, we also oppose extremism, terrorism and fundamentalism coming into Afghanistan from outside. We have one page where there is a tremendous desire for friendship and the need for each other. But there is the other page, of the consequences if intervention continues, cross-border terrorism continues, violence and extremism continue. Afghans will have no choice but to stand up and stop it."

Among Americans, only the special envoy of the US president to Afghanistan and a good friend of President Karzai, Zalmay Khalilzad, has shown any concern about the recent developments. Khalilzad has little choice but to keep up a bold front to the Afghans, telling them how his bosses in Washington are doing their best to rebuild Afghanistan, and attributes the present crisis to the security situation. Like everyone else, Khalilzad has little in reality to offer and, given the opportunity, falls back on what "must be done" and "should be done". At a July 15 press conference at Kabul, Khalilzad said every effort has to be made by Pakistan not to allow its territory to be used by the Taliban elements. This "should not be allowed", he said. "We need 100 percent assurances [from Pakistan] on this, not 50 percent assurances, and we know the Taliban are planning in Quetta."

What is happening? Both Hagenbeck, who boasts to the media about the high quality of his intelligence, and Khalilzad, who is unquestionably in a position to know, have stated that the Taliban and al-Qaeda are being nurtured, not in some inaccessible terrain along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border but in Quetta, the capital of Pakistan's Balochistan province where the Pakistan Army and the ISI have a major presence. Yet, President Bush and his neo-conservative henchmen have remained strangely quiet, allowing Pakistan to strengthen the Taliban in Quetta, and, as a consequence, re-energize al-Qaeda -- the killers of thousands of Americans in the fall of 2001.

Recall for a moment: Following the September 11 terrorist attacks in the United States, no other terrorist was portrayed by the United States as more dangerous than al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden and no other Islamic fundamentalist group was presented to the American people as more despicable than the Taliban. Within a month the United States invaded Afghanistan to "take out" the Taliban, al-Qaeda and bin Laden, while the world lined up behind the new anti-terrorist messiahs from Washington, providing it the necessary moral and vocal support. Why, then, is Washington now weakening President Karzai and allowing the strengthening and re-emergence of the Taliban?

Karzai shared with Ahmed Rashid his belief, like that of the average Afghan today, that the answer to that question lies in an understanding reached between the United States and Pakistan during Musharraf's visit to Camp David, that Afghanistan could be, in effect, "sub-contracted" to Pakistan. Karzai also told Rashid that Musharraf's critical remarks about the Karzai regime during his visit to the United States reminded him of the pre-September 11 days when Pakistan was fully backing the Taliban and exercising ever-more-strident control over Afghanistan. Musharraf had said, among other things, that the Afghan president does not have much control over Afghanistan beyond Kabul. But, Karzai added in the interview with Rashid, no matter what the outsiders are planning or plotting, as of now, "I want nobody to be under any illusion that Afghanistan will allow any other country to control it." Is Karzai overreacting? Most likely, he is not. He has seen the writing on the wall. It is arguable whether the Taliban's return to power is inevitable, but there is little doubt that under the circumstances it is very convenient for the US.

Bowing to realities

To begin with, it was clear from the outset that the United States never really wanted to be in Afghanistan. It was basically a jumping-off point for the "big enchilada", the re-shaping of the Middle East's politics and regimes. The Afghan reconstruction talk was mostly wishful thinking. For anyone familiar with present-day Afghanistan -- its security situation, the drug production and trafficking, its destroyed infrastructure, its rampant illiteracy and poverty -- its reconstruction by foreigners is either a dream or a string of motivated lies.

Now, after a half-hearted effort that lasted for almost 18 months, the Bush administration has come to realize that it is impossible to keep Pakistan as a friend and simultaneously keep the Northern Alliance-backed government in power in Kabul. The "puppet" Pashtun leader in Kabul, Hamid Karzai, does not have the approval of Pakistan and the majority of the rest of the Pashtun community straddling both sides of the Pakistan- Afghanistan border. So, either one has Pakistan as a friend with an Islamabad-backed Pashtun group in power in Kabul, or one gets Pakistan as an enemy. There should be no doubt in anyone's mind how the Bush administration would act when confronted with such a choice.

Secondly, look at the Northern Alliance (NA) allies. The best ally of the NA is Russia, the Bush administration's key contestant for supremacy in Central Asia. In the 1980s, the United States spent billions of dollars to get Afghanistan out of the Russian orbit. It is ridiculous to believe that the Bush administration would act differently now to protect the NA and Karzai. Much better is to have Afghanistan sub- contracted to Pakistan and keep the Russians at bay, than to yield ground to Moscow, who is hardly friendly to Pakistan.

Thirdly, the NA, and particularly the Shi'ites of the Hazara region of Afghanistan, are close to Iran. Iran is building a road which will connect the Iranian port of Chahbahar to the city of Herat in central Afghanistan and link up with Kandahar in the southeast. While this is going on, some neo- conservatives in Washington are screaming for Iranian blood. Even if the Bush administration is not quite willing right now to spill that blood, it is nonetheless a certainty that Washington will be more than eager to see the Iranian influence in Afghanistan curbed. If the NA-backed Karzai government stays in power for long, Iran would most definitely enhance its influence. The Taliban do not want that and they have sent a message recently by slaughtering the Shi'ites in Quetta with the full knowledge of the Pakistani authorities. Besides being anti-Russia, the Taliban are also anti-Shi'ite, or anti-Iran. This added "virtue" of the Taliban has not gone unnoticed in the corridors of intrigue-makers in Washington.

Finally, there is the India factor. A minor factor, it does, however, come into play in calculating the pluses and minuses of the resurgent Taliban option. The Bush administration wants closer relations with India -- not on New Delhi's terms, but on Washington's terms. Indian activity in Afghanistan has increased multifold since the Karzai government came to power in the winter of 2001. These developments are being eyed suspiciously by Islamabad. While Washington would not make a federal case out of it, it surely does not like to see India forming a strategic alliance with Russia and Iran in Afghanistan. Washington would rather like to break such an alliance quickly, particularly if its ally, in this case Pakistan, wants such an alliance broken. Significantly, a well-connected relative of Musharraf, Brigadier Feroz Hassan Khan, formerly at the Wilson Center and now a fellow at the Monterey Institute of International Studies, addressed these issues directly in a recent publication.

Not just whistling in the dark

In the January issue of Strategic Insight, a publication for the Center for Contemporary Conflict, Khan observed: "In Iran, President Khatami is moving in tandem and cooperation with Pakistan in supporting the Karzai government as manifest in the recent visit to Pakistan. However there are hardliners in Iran who would want to continue with the old game of supporting warlords and factions and consider Pakistan as rival vis-a-vis Afghanistan, and who are still suspicious of the Saudi role. Iran is pitching its bid, by constructing a road from Chahbahar Port in the Persian Gulf through Iran's Balochistan area to link up eventually with Kandahar in the hope of `breaking the monopoly of Pakistan'. Afghanistan is currently sustained primarily through the Karachi-Quetta/Peshawar routes -- Bolan and Khyber passes respectively -- which has provided Afghanistan with trade and transit with the outside world for centuries."

Furthermore, Khan pointed out, "Russia remains involved with the major warlords [of Afghanistan]. One such warlord, Rashid Dostum, was recently on a shopping spree for arms and equipment from Moscow. Russia believes it has its own experience and expertise in Afghanistan and must reestablish its interests. Given the history, Pakistan is very uncomfortable with this development."

Of course, the Khan's treatise would not have been complete without pointing to the devious role of the Indians in Afghanistan. He said: "India is a major proactive player now. It is providing well-coordinated military supplies to the Northern Alliance thorough the air base in Tajikistan. This includes weapons, equipment and spare parts aimed at strengthening those elements that had become the sworn enemies of Pakistan during the Taliban's rule. Fear in Pakistan is that despite Afghanistan's changed policies, some elements still hold a grudge against Pakistan and would be willing to do India's bidding. This would bring the India- Pakistan rivalry into the Afghan imbroglio."

It is safe to assume that Khan, who has an extensive background in arms control, disarmament and international treaties, and who formulated Pakistan's security policy on nuclear war, arms control and strategic stability in South Asia, is not merely whistling in the dark.

The terms of convenience

Now the question remains, what might Pakistan be expected to deliver in return for the Bush administration granting it control over Afghanistan once more? In the real world, Pakistan can help the United States significantly. It has already agreed not to provide nuclear technology to Islamic nations. Musharraf may have to give the United States control of its nuclear research facility, among other things. More important will be to hand over Osama bin Laden to the United States and send two brigades of Pakistani troops to Iraq to help out the beleaguered US troops there. The arrest of Osama would surely justify the US mission to Afghanistan, and could set the stage for America's eventual withdrawal from that country. Another likely item on the agenda is Pakistani recognition of Israel.

Would this new arrangement of "sub-contracting" (to use Karzai's apt term) Afghanistan to the Pakistan-Taliban combination complicate the already complex situation any further? Probably not. It was evident in October 2001, when the United States went pell-mell into Afghanistan with the help of the Northern Alliance, that America's hastily- organized arrangement there was unsustainable. It was clear that no matter what Islamabad says, or how much pressure is brought to bear on it, Pakistan has absolutely no reason whatsoever to agree to such an arrangement.

Washington came to appreciate the non-sustainability of this arrangement when Musharraf, in a sleight of hand, brought the Muttahida Majlis-e Amal -- the MMA, also known as "Musharraf, Mullahs and the Army" -- to power in the two provinces bordering Afghanistan. At that point, Karzai's tenure as president of Afghanistan shrank abruptly, and Washington deemed it time to give up the "Marshall Plan for Afghanistan" and settle for next best -- Taliban rule in Afghanistan under Pakistani control, once again.

Copyright © 2003 The Asia Times

Unreconstructed

By Barry Bearak, The New York Times, June 1, 2003His Excellency Ismail Khan -- ruler of the ancient city of Herat, governor of the province, emir of the western territories and commander of Afghanistan's fourth military corps -- seemed fascinated by the woman with no arms. "It's amazing -- she eats with her toes," he said, looking my way.

The emir had allowed me to sit at his shoulder during his weekly public assembly, when hundreds of supplicants come to the great hall of the governor's compound and plead for him to intercede in their behalf. As usual, Ismail Khan was wearing a spotless white waistcoat, whiter even than his famous fluff of beard, thick as cotton candy. He sat at a simple desk beneath the adoring light of a grand chandelier. Uniformed men hovered nearby, ready to be dispatched on sudden errands. Other aides in suits and ties periodically brought papers for him to sign, removing each one the instant the emir's signature was complete and then bowing before backpedaling away.

The armless young woman, disabled since birth, was herself dutifully respectful as she confided her problems with humble words and earnest genuflections. Her voice was a nervous chirp, her eyes hidden behind the meshed peephole of a burka. She asked for nothing more than money for medication. But Ismail Khan, pitying her disability, thought she should be requesting much more. "Why aren't you married?" he asked. "If you want, I will find you a mujahid to serve you."

The woman did not know quite how to react. "I love my father," she said hesitantly.

But the emir grew ever more pleased at his own benevolence. His mind was made up. "If you marry, it would be better," he said.

Hour after hour it went on, the needy coming forward one at a time from the cushioned chairs of the waiting area, alternately a man and then a woman, all eager to hear a few transforming words. A few petitioners were keen businessmen, wanting land for a factory or permission to open a bazaar. Other people required the emir's decisive arbitration about property disputes or jailed loved ones or reneged marriage arrangements. But mostly, the hopeful were the pitifully poor, often telling stunning tales of personal tragedy, only to then make the most modest of requests: a visa, a bag of rice, use of a telephone, oil for their lanterns.

In this lordly fashion, acting in the manner of the great caliphs, Ismail Khan dispensed a day's worth of practical wisdom and petty cash. It was a remarkable display of personal might -- and one quite in keeping with his busy personal campaign to improve Herat itself, the only major city in the nation where significant reconstruction has taken place. Under the emir's guiding hand, roads have been paved, irrigation channels restored, schoolhouses rebuilt. Clean water has been supplied to most neighborhoods... Soon, Herat will be the nation's only city with around-the-clock power. New parks adorn the cityscape, including two that have large swimming pools and brightly colored playground equipment -- surreal novelties in so woebegone a country. "Judge for yourself," the emir said one sunny afternoon when he was particularly given to boasting. "Where in Kabul will you find families in a park after 10 p.m.? Where is there even a park?"

A year and a half has now passed since American bombers changed the course of this nation's civil war, a year and a half since the Taliban were forced from their commanding perches to lurk now in hideaways; a year since President George W. Bush pledged something akin to a Marshall Plan for Afghanistan. The reconstruction was to be a mammoth effort in the spirit of American generosity to Europe after World War II, he said, a way to "give the Afghan people the means to achieve their own aspirations."

It would be nice to report that Ismail Khan's industriousness typifies a nationwide revival. But the rebuilding of Afghanistan -- among the world's poorest countries even before it suffered 23 years of war -- has so far been a sputtering, disappointing enterprise, short of results, short of strategy, short, most would say, of money. As for the emir, rather than a lead character in the restoration, he is actually a foremost symbol of its affliction.

Nation-building, scorned by George Bush the presidential candidate, has now become the avowed obligation of George Bush the global liberator. The problem is that nations, like so many Humpty Dumpties, are troublesome to put back together again. The challenge -- whether in Afghanistan or Iraq -- is more than brick and mortar, more than airwaves and phone lines; this is not the kind of carpentry required after a hurricane.

Afghanistan has been in atrophy for a generation, with institutions in decay, educations in eclipse, the entire society tossing and turning in a benumbing nightmare. Like so many of its people, the nation is missing limbs. There is an overabundance of guns but only the beginnings of a national army and a police force. Elections are scheduled for next year, but there are no voter-registration rolls, nor is there even a working constitution. Entrepreneurs want to think big, but there are no commercial banks to make loans. Much of the land is fertile, but the only major export is the raw opium used in the criminal drug trade. Civil servants have again begun to collect salaries, but pay remains a mere $30 to $40 a month, and many workers rely on tolerated corruption to feed their families.

In so many ways, time seems to have halted in the 1970's, and now the past fails to flow logically into the present. Documents are copied with carbon paper and then held together by straight pins; staplers are largely unknown. Traffic flows in the right-hand lane of the roads, though these days most vehicles have steering wheels for left-side driving.

The country has an interim government, but it is much less than the sum of its parts -- and those parts are largely controlled by warlords like Ismail Khan in the west, Abdul Rashid Dostum and Atta Muhammad in the north, Gul Agha Shirzai in the south and Haji Din Mohammad and Hazrat Ali in the east. In a hasty postwar fusion of distrustful factions, these men -- all A merican-armed allies against the Taliban -- were welcomed into the incipient government and given official titles. And while each expediently mouths allegiance to President Hamid Karzai in Kabul, they still maintain their own militaries and collect their own revenues.

"Emir" may well be Ismail Khan's favored title. (His aides insist he be addressed as "your excellency, emir sahib.") But what gives him legitimacy in the current setup -- as well as phenomenal resources -- is his designation as governor of Herat, one of the great junctions on the old Silk Route and still the nation's richest turf. Most goods entering Afghanistan arrive by way of Iran, traversing Ismail Khan- controlled stretches of highway on their way to smugglers' bazaars in Pakistan. Truckers are obliged to pay duty at the Herat customs house, and while by right all collections belong to Afghanistan's central treasury, the emir has remitted only a fraction of a daily take variously estimated between $250,000 and $1.5 million. It is as if the governor of New York also declared himself the emir of New Jersey and Connecticut, keeping federal taxes from the region for his own purposes.

I visited the customs house and its surroundings. Not far from the main buildings was the largest used-car lot I had ever seen, with dusty autos and S.U.V.'s parked along both sides of a mile-long strip, each row dozens deep rising into the hillsides. Most of the vehicles were Japanese, shipped through Dubai and then driven or hauled to Herat. Merchants wearing long-tailed turbans used tents as offices, bellyaching about sagging profits. It was bad enough, they said, to be harassed for a relentless sequence of bribes. But now customs fees themselves had recently doubled, amounting to as much as $2,000 for a late-model Land Cruiser.

During a quiet moment in the governor's compound, just after the emir had returned from his midday prayers but before he resumed seeing his supplicants, I politely asked him, "About how much customs revenue do you collect, emir sahib?"

"Maybe you can't believe this," he assumed correctly, "but I really don't know."

Warlords are not the only ones reluctant to turn their cash over to Kabul. So are most of the donor countries providing aid. "None of it goes through the government," said Elisabeth Kvitashvili, the acting mission director in Kabul for the United States Agency for International Development. "If we felt the government and the ministries had the capacity to handle the money in a manner that would satisfy the U.S. taxpayer, we'd give it to them, but that's a big if." USAID has bookkeeping standards unlikely to be met by long-dormant Afghan bureaucrats, she said. Instead, assistance is channeled through the United Nations, outside contractors or private aid agencies -- the so-called nongovernmental organizations, the NGO's.

America has two ambassadors in Kabul. William Taylor Jr., the "special representative for donor assistance," calls himself the "lesser" of the titleholders. He is a self-described optimist who nevertheless said that if some highly visible reconstruction projects do not start happening soon, both the Afghan and United States governments will be "in trouble."

By Taylor's math, America made $649 million available to fghanistan in fiscal year 2002, which ended in September; in 2003, the amount should exceed $1.2 billion. While a hefty sum, even the latter amount is hardly Marshall Plan size. Indeed, it roughly equals the cost of a single B-2 stealth bomber; it is about the same amount the United States military spends in Afghanistan every month. But America never intended to go it alone, as it did in Iraq. Reconstruction was supposed to be a multilateral effort.

In January 2002, when the post-9/11 world still held Afghanistan near the center of its orbit, a conference took place in Tokyo. Fighting was still going on outside Kandahar, the Taliban's main stronghold, but there was already a sense of urgency to the matter of rebuilding the country. Unfortunately, with events happening in rapid flash, there were also many unknowns. What were to be the goals of this reconstruction? Was the nation merely to be restored to entrenched poverty, or was the objective something more?

No one knew the parameters of Afghanistan's many crises. Security concerns had long kept researchers from the field. What were the conditions of rural access roads and irrigation systems? What were the rates of malnutrition, TB and infant mortality?

Analysts from the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the United Nations Development Program had hurriedly prepared a preliminary assessment. Though there were caveats about the guesswork involved in their 59-page report, they did dare to estimate costs: the bill could range from $1.4 billion to $2.1 billion in the first year, $8.3 billion to $12.2 billion over five years and $11.4 billion to $18.1 billion over 10 years.

But when the donors -- a dozen or so nations, the European Union and the World Bank -- actually opened their wallets, their generous impulses fell short of their compassionate rhetoric. Pledges of grants and loans -- made for periods of one to five years -- totaled $5.2 billion, only about 60 percent of the low-end five-year projection. Still, the help was beyond anything Afghanistan had received since the days of the cold war, when the tenacious mujahedeen, revered in the West as front-line fighters against Communism, were lavished with billions in weaponry. Welcoming the pledges, a spokesman for the transitional government said: "We're thrilled. Every single dollar is appreciated."

But soon the thrill was gone. Some pledges were slow to be paid, and much of the money went for food and medicine and blankets and tents and firewood and all the other things war- bedraggled, drought-parched, morbidly poor people desperately need. Refugees were flooding back across the border. By last fall, nearly two million had returned, some rudely hurried on their way by Pakistan and Iran, which had proved impatient caretakers, others emboldened by optimistic radio broadcasts. The world was promising to rebuild their homeland. They did not want to miss out.

Of course, this reverse migration only added to the glut of the hopelessly poor. These people also needed emergency help. During the first year after the war, short-term relief efforts consumed 50 to 70 percent of the "reconstruction" aid, depending on how the numbers are tallied. The transitional government certainly welcomed the assistance but objected to its being credited against the pledges made in Tokyo. Wasn't that money meant for hospitals and not Band-Aids? In fact, as time passed, that $5.2 billion began to seem smaller all the time. CARE International, the NGO, issued a study comparing per capita aid provided in recent postconflict situations. Afghanistan fared poorly next to East Timor and Rwanda and did even worse against Kosovo and Bosnia. Government officials often quoted the numbers, sounding wounded -- and even cheated -- reminding foreigners of Afghanistan's sacrifices against Soviet invaders and fanatic terrorists. It was hard to quarrel with the umbrage. Indeed, Robert Finn, the "greater" of the two American ambassadors, told me that the discrepancies in aid were all the worse because relative costs were higher in Afghanistan. "There is almost no infrastructure left," he said. "And mostly, there was never any infrastructure, electricity, water. You have to supply everything." He said that only 3 of 32 provinces were linked by telephone to the capital and that "the country was absolutely medieval in some places."

But what most annoyed the Afghans was how they were repeatedly sidestepped in the cause of their own resurrection. Though they were consulted about projects, when it actually came time to begin one, the money went into other hands. The word "capacity" was always invoked, as in, "The U.N. and the NGO's have the capacity to do the job, and you don't." Much of the donors' thinking was realistic, of course. Clearly, the aid agencies -- repeating familiar tasks year to year in country after country -- knew better how to satisfy vigilant auditors in Brussels or Washington.

And just as clearly, the Afghans were very often flummoxed while trying to kick-start an old wreck of a government. The Ministry of Finance was headquartered in a huge pinkish building, but the heating system was shot, the roof leaked and only one bathroom functioned. "Physically it looked like a stable," Ashraf Ghani, the finance minister, told me in an interview. His wife, sitting nearby, added, "It smelled like one too."

There was certainly no shortage of civil servants. Estimates put the number at 250,000, though their attendance had become as intermittent as their wages. International business consultants -- contracted by USAID -- were goggle-eyed at what they found in government offices. The central bank operated without a working balance sheet. Payroll records were scarce. When salaries were paid, there were no checks or vouchers. Cash was hand-carried to each province. The "lab" at the Kabul customs house -- the main line of defense against infestations in fruit and vegetables -- did not have a single beaker or test tube; it consisted of five bored men sitting in an old shipping container sipping tea.

"The needs are so great; everywhere you turn, it's a priority," said Lakhdar Brahimi, the Algerian diplomat who oversees the United Nations presence in Afghanistan. He is a veteran global troubleshooter who has also worked in Haiti and South Africa. In the late 90's, he tried to broker a peace between the Taliban and the fast-collapsing forces of the resistance, many of whom -- through the miracle elixir sometimes referred to here as vitamin B-52 -- are now central figures in the government.

When I asked Brahimi what the biggest accomplishments of reconstruction were, he answered, "Probably not very much." For him, the most important rebuilding project was bringing security to the country, and that had yet to happen. Without it, he said, everything else was in jeopardy. "The Taliban have been routed; they have been expelled from the capital, but they have not been defeated, or at least they have not accepted their defeat."

As he and I talked, there was fresh news about a particularly alarming murder. Gunmen at a roadblock near Kandahar had ordered people out of their vehicles, which in itself is a common, perhaps even expected practice along some roads. But these thugs let their Afghan captives go, while shooting a Salvadoran water engineer from the Red Cross. The next day, a Taliban commander phoned the BBC and announced a jihad against "Jews and Christians, all foreign crusaders." Two weeks later, an Italian tourist was gunned down.

The recent attacks have not been limited to foreigners. Snipers have started to target Afghans employed to clear land mines from the terrain. Ambushes occur almost daily now, causing many aid groups to further restrict already limited labors. More than that, the incidents re-emphasize a chilling truth in a violent, gun-toting land. Any number of major reconstruction projects could be stopped with a few well- aimed bullets.

The American-led coalition against terrorism keeps more than 11,000 soldiers in the country, including 8,500 Americans. But their job is combat, chasing after vestiges of the Taliban and Al Qaeda. Brahimi is talking about something else, the confidence inspired by basic police work. From the start, both he and the new government have pleaded for an expanded international force to deter robberies on the roads and pillaging by vengeful warlords with ethnic scores to settle. A security force of 5,000 multinational troops -- currently commanded by the Germans and the Dutch -- is stationed in Kabul but does not venture into the provinces. Early on, the United States opposed any expansion of this detachment, and while lately the American attitude has been more conciliatory, American officials aren't in a hurry to provide troops. "You know very well that in a situation like this, unless the Americans say, `This is needed and we will support it,' it will not happen," said Brahimi. "If I tell you we have a security problem, you tell me, `No, it's too dangerous for our soldiers' -- who are trained, who are armed. Don't you think it's also too dangerous for me?"

Most non-Afghans restrict themselves to Kabul. The capital's population has swelled to more than three million, and while most new arrivals are returned refugees -- the bulk of them destitute -- foreigners are a conspicuous presence. Kabul is now a Western-friendly host. Hyatt International has agreed to manage a luxury hotel to be built near the United States Embassy. Souvenir shops and rug merchants have multiplied tenfold. Brand-new carpets are spread across the streets to be run over by cars, the traffic rapidly "aging" the wool for wealthier customers who prefer antiques. Expensive restaurants with international cuisine have opened. At a new spot called B's Place, the maitre d'hotel announced fish Valencia as the chef's daily special and suggested an accompanying wine, something forbidden under the Taliban no matter what the vintage.

Without any whip-wielding religious police officers roving around in black pickup trucks, Kabul's high quotient of dread has vastly declined. About half the women in the streets now shun the burka, though most continue to keep their heads reverently covered. Girls as well as boys are free to attend school, albeit terribly overcrowded ones. Satellite TV dishes, necessarily camouflaged under Taliban rule, openly bloom from the rooftops. Entire markets are devoted to music and movies sold on bootlegged CD's. There is a bustle to the city. Traffic congeals into jams at predictable rush hours.

Soon after arriving, I looked up an acquaintance, Sabir Latifi, a businessman with a great nose for the aroma of money. He has always had the right contacts in the right places, even when the Taliban governed, and as usual he greeted me with a hug as his "first best friend," a distinction I no doubt share with hundreds of others. During the past year, Latifi has opened two guest houses, a restaurant and an Internet cafe, as well as businesses in advertising, real estate, tourism and computers. But the really big money was eluding him, he complained gravely. He lacked financiers to stake him in the bottling of mineral water, fruit juices and soft drinks. He needed a packing plant so he could export produce. "But this is a country without any banking laws, so the big international companies don't want to invest," he said. And that was not the worst of it. Hundreds of millions of dollars in foreign aid was flooding into Afghanistan only to stream right out again. Humanitarian agencies with hefty start-up costs were all spending money overseas, buying cars, computers and generators from international suppliers. Construction contracts were being won by foreign companies. "Where is the money for us Afghans?" he wanted to know.

This was a question ruefully asked throughout the country. Western Kabul, the most-bombed-out part of the capital, still has the postapocalyptic look it acquired in the early 90's when rival Afghan armies used it as a battleground. What is left are the mutilated carcasses of buildings, their roofs gone, walls chewed away, columns sticking up like stalagmites. The neighborhood is now a favored sanctuary of the former refugees. Seventy families live in the remnant hollows of a sandal factory. One recent morning, a 6-year-old boy named Munir wandered sleepily out of a third-floor doorway and into the empty air a few feet away, falling to his death.

"We've been told nothing but lies," insisted Rozi Ahmad, one of the boy's relatives, speaking for a collection of nodding men standing behind him inside the factory. Buoyant talk on the radio had enticed them to come back. And though their children now carry bright blue Unicef book bags to reopened schools, and though they occasionally receive a 50-pound sack of free wheat, most feel deceived. "Even if you drive, you see the destroyed roads are the same, unchanged, no repairs," Ahmad said, extending an arm toward the horizon. "There was supposed to be billions of dollars. How has it been spent?"

Indeed, there is a notable lack of edifices to show for the money that has arrived so far -- a total of $1.8 billion, according to a government agency that coordinates with the international donors. The most-talked-about project is the repair of one of the world's worst highway systems, the torn-up circle of bone-jarring bumps and car-swallowing ruts that connect Kabul, Kandahar, Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif and Jalalabad. Promises for financing have been made by the United States, the European Union, India, Iran, Japan and the World Bank. But little work has begun.

"For a road to be built properly, it must have a proper design, and a design is time-consuming," Karl Harbo, head of the European Union's aid office in Afghanistan, told me. He said planners were cutting as many corners as possible, but the job will be especially toilsome because of "sanded-up culverts" and "broken retaining walls," to say nothing of land mines. "You don't want to build a road that will need repair in two or three years."

Ambassador Finn said much the same thing about the entire reconstruction process: "It's like building a house. You have to figure out what you're doing and gather materials. Building a country is the same thing."

The road is highly symbolic to Hamid Karzai, Afghanistan's dapper, patrician president. Last year, during a visit to America, he and George Bush shook hands on a pledge to get the project finished. Karzai remains disappointed. "Reconstruction in the manner we wanted it, with the speed we wanted it, has not taken place," he said, calibrating his words, not wanting to let his frustration stray into ingratitude. "In the eyes of the Afghan people, reconstruction means visible permanent infrastructure projects" like roads, dams and power plants. "The Afghan people don't seem to like these quick-fix projects, where you give them a dirt road and the next rainy season it is gone away."

In September, an assassin's bullets barely missed Karzai as his car moved through a crowd in the middle of Kandahar. Just months earlier, he accepted American bodyguards after one of his vice presidents was shot dead. Detractors insist that Karzai is a lackey for the United States and the possessor of so little power that he is little more than the mayor of Kabul. But those criticisms are overdrawn. He has managed to hold together a multiethnic cabinet in an ethnically divided country, and his closeness to the Americans and the United Nations actually endows him with clout. Though he has often seemed reticent to exercise his power, in mid-May he did try to bring opponents in line with an artful use of petulance. He threatened to quit.

"Every day, the people of Afghanistan lose hope and trust in the government," he complained in a speech. The catalyst for this public lament was the threadbare treasury. Once again, civil servants were going without pay. We have the funds, Karzai said: "The money is in provincial customs houses around the country." He put the total at more than $600 million. Unfortunately, he said, very little was being forwarded to Kabul.

Karzai then held an emergency meeting of governors and warlords from the border areas, including Ismail Khan. He got them to sign an agreement promising not to hoard the revenues or launch their own military attacks. Such promises have been dutifully made before, only to be selfishly ignored later.

But merely getting Ismail Khan to attend was a victory of sorts. He isn't always so cooperative. The month before, all 32 governors were summoned to the capital. The president and the interior minister chewed them out. You need to be more responsible about security, they were told; you need to clamp down on farmers growing poppy, who have again turned Afghanistan into the breadbasket of the heroin trade; you need to turn over your revenues. Three governors were not present. Two had phoned in with legitimate excuses. Ismail Khan chose to send his deputy, who merely said that the emir extended his regrets.

Why not just fire someone like Ismail Khan? I asked Karzai.

"Governments cannot behave in a trigger-happy manner," he told me, saying that it was far too soon for such confrontations. "Governments have to think and then decide."

The political part of reconstruction is at least as important as the physical -- or so I was constantly told. It was hard to disagree. The latter, no matter how well built, won't last very long without the sanctuary of the former. The Kabul government must prove that it can assert authority -- protect people, collect taxes, dispense jobs, build things. For now, warlords big and small control their customary fiefs. "There's no law," Brahimi of the United Nations said, summing up. "You're at the mercy of the commander, who will at any time come and demand money, take your property, force you to give your daughter in marriage."

President Karzai is a Pashtun, the nation's largest ethnic group. But the defense and foreign ministries and the intelligence service are dominated by Tajiks from a single district, the Panjshir Valley. One of them, Defense Minister Muhammad Qasim Fahim, headed the Northern Alliance and marched into Kabul with his troops nine weeks after 9/11. Many Afghans consider him to be nothing more than a warlord himself. His large, well-equipped army remains bivouacked in and around the capital.

Last June, during the loya jirga, or grand council, Karzai was formally chosen as interim president, to hold office until a new constitution could be written and a national election held in June 2004. Many Afghans thought this was an opportune time to rid the country of its regional chieftains. Indeed, with so many American troops deployed, the warlords themselves were anxious about surviving. But the Americans still had use for the commanders in the quest for Al Qaeda, paying some of them to put their soldiers into the field. And at the time, Karzai was more concerned with finding a balance among rival ethnic groups. He wanted to pacify the powerful, not confront them.

Though ethnic tensions remain, a new fault line has opened that may be equally divisive. Welcomed into the government have been several "neckties," Western-educated exiles who have come back to assume high posts. Karzai seems to rely on them more and more. "Without Afghans who have been trained in Europe and America and other parts of the world, Afghanistan cannot go forward," he told me. Who else has the education? he asked. Within the country, a generation has passed without the development of new skills. "It's a gap. It'll take God knows how many years to fill."

The most powerful "necktie" is Ashraf Ghani, who is not merely the minister of finance but also the president's closest adviser and a man with a hand in almost everything. Surpassingly erudite and surpassingly fond of displaying it, Ghani, 54, has a Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia. He taught at Johns Hopkins. He worked at the World Bank for 11 years, traveling widely, studying third-world economies, managing the reform of the Russian coal industry. He is, by virtually all accounts, a brilliant analyst with a warehouse memory. Also, by virtually all accounts, he is an acerbic man who does not suffer fools gladly and defines that category most broadly. "He has that sting-y tongue," Karzai said, well aware of what he has unleashed. "It hurts." Several ministers have grown to loathe Ghani. All seem to fear him.

The finance minister comes from a well-known, well-heeled family of the Ahmadzai, the largest of the Pashtun tribes. Many of his ancestors served Afghanistan's royalty, including a great-great-grandfather who was executed. "They said his neck was too precious, so they hung him with a silk rope," Ghani told me one evening at his home in the capital's best neighborhood. I had been eager to meet him and found him in a relaxed mood, somewhat fatigued but charming. The tart side of his tongue made no appearance. His wife, Rula, who is Lebanese, sat with us as her husband narrated a short personal history. "My family has been dispossessed five times in five different generations," he said. Both of his grandfathers served as mayors of Kabul. "Every male member of my family was imprisoned" when the Communists took over the country in 1978, he said. "The women had to sell the bulk of the land to keep the men alive." At the time, he was studying abroad.

His exile lasted 24 years. Brahimi named him as a special adviser soon after 9/11. The prickly anthropologist immediately became the bridge between Afghanistan and the foreign money. Ghani can talk in the mannered jargon of the international lenders, and he has been able to persuade more of them to give their grants directly to the government. At the same time, he has assumed the role of cabinet watchdog, using the budget as a hammer against any loose accounting byfellow ministers. He sometimes berates them in cabinet meetings. "If any expenditure is declared ineligible, meaning not according to the rules, I cut exactly the same amount from their budget," Ghani said with a chuckle. "And if it repeats, a second offense, I'll cut double their money." Opponents think him power-mad.

For Ghani to truly control the nation's treasury, he will have to humble the warlords and collect all those customs fees. He and another "necktie," Interior Minister Ali Jalali, have even spoken of a highway patrol that would accompany cargo-carrying trucks in a caravan from the border, bypassing all illegal collection points along the way. Ghani has also visited some of the warlords himself, staking claim to funds. He was greeted warmly by Ismail Khan but then sent home with the promise of only $10 million. "I have a delegation in Herat, working the numbers," Ghani told me rather legalistically. If Ismail Khan "doesn't remit the budgetary resources, then he would be an outlaw."

But what sheriff would arrest the emir?

These men are two of the stranger bedfellows that lie in Afghanistan's future. Ismail Khan, 56, is a short, stocky man whose face pairs a knowing smile with a fierce stare. He wears a black, gray and white headdress that perfectly accompanies his dark eyebrows, gray mustache and snowy beard. His portrait appears nearly everywhere in Herat. Patriotic posters often couple him with Karzai or the war hero Ahmad Shah Massoud, though Khan is always the one in the foreground.

Back in 1979, Ismail Khan was merely a junior artillery officer. He became involved in a mutiny against the Communists then ruling the country. And later, after the Soviets invaded, he became a guerrilla commander. By dint of battlefield success -- as well as of the coincident deaths of other contenders -- he emerged as the leader of the resistance in Afghanistan's west and a self-proclaimed emir. After the Soviets skulked away in 1989, he assumed the governorship of Herat, his popularity ebbing and flowing during a turbulent time of civil war. He was in an ebb phase when the Taliban -- then known as pious champions of law and order -- succeeded in taking the city in the fall of 1995. The emir escaped to Iran, and when he later returned to fight, he was the victim of an ally's betrayal and ended up as his enemy's most famous prisoner. He spent more than two years in a Taliban jail, often manacled in a zawlana, an iron device that hitched his neck to his wrists and ankles. A young Talib intelligence officer helped him in a nerve- racking escape through the desert. Ismail Khan's getaway vehicle hit a land mine, and his leg was broken in the explosion. The Taliban were furious when the wounded emir surfaced safely, again in Iran.

Ghani, by contrast, is clean-shaven, with the frail look of a professor who spends too much time indoors. Two operations for cancer have removed most of his stomach. With so much of his insides cut away, he is forced to eat frequently in small quantities, continuously irrigating himself with fluids. Kidney stones have tormented him. He complains of constant pain, though this does not seem to keep him from working 16- hour days. His speech is deliberate, often a monotone, and his reservoir of intellect provides him his own kind of forcefulness. Despite being the consummate "necktie," these days he wears loose-fitting Afghan clothes and constantly fingers a strand of prayer beads.

Ghani allowed me to attend some of his meetings one day. In the morning, his large office filled with half a dozen key staff members, all seated on sofas and armchairs. Conspicuously, most were Westerners -- those consultants paid for by USAID, dressed in conservative business suits and shined shoes. "We've been in the Kabul customs house from one end to the other, and we have a very good idea what's happening there," one reported. Not surprisingly, they had found gross inefficiency amid grosser corruption, or perhaps it was the other way around. Computerization was prescribed. Ghani said he would "talk to the Koreans" about it. They sounded like commandos plotting a takeover.