FEDERAL currency was in short supply during the Great Depression, so local banks, stores, town governments and others with initiative issued their own scrip. In Springfield, Massachusetts, the publisher of the Springfield Union News, Samuel Bowles, began to pay his employees in scrip redeemable at local stores, which used it to pay for advertisements in the newspaper. Seeing Bowles regularly and knowing his character, locals developed more confidence in his dollars than federal money, which helped the Springfield economy stay relatively healthy during those hard times.As production for World War II and President Franklin Roosevelt's work programs helped get the national economy back on its feet, local money faded away. But the last few years have seen a resurgence in local currencies, which are being used to keep money in the community and out of mall-based chain retail stores that decimate downtowns and force longtime merchants out of business. Local currencies affirm the value of labor among everyone in the community and reaffirm connections frayed in a mobile, increasingly impersonal society.

"The current revival is coming out of a sense of alienation with the global economy," says Susan Witt, executive director of the E.F. Schumacher Society and editor of its Local Currency News publication. "Scrip is deliberately limiting choices to local sources. It's also limiting choices to people you know, people you have a face-to-face relationship with -- those you see at PTA and Board of Selectmen meetings or at work. A yearning for connectedness is behind this revival."

The resurgence of local money flies in the face of global trends such as the consolidation of national currencies into one unit in the European Union. "Europe is catching up to the U.S., where the monetary destinies of hundreds of millions are controlled by fewer and fewer authorities," notes Paul Glover, founder of Ithaca HOURS, the local currency of Ithaca, New York. "When decisions are made by people far away with different priorities, many local economies become vulnerable. Farmers in this country, for example, have long understood that money moves from rural areas to major money centers -- with deadly effect. Local and regional money can revive deflated, discarded economies, both rural and urban."

The standardized products generated by multinational production hurt local economics and reduce people's sense of connection with a community, says Witt. "So many of our goods now are cookie cutter goods," she explains. "We don't know the story behind them. We don't know what our money is doing -- it could be invested in wheelbarrows in Brazil or paper chips in North Carolina or a shoe factory in Taiwan using toxic materials and harming workers. When you buy a local product, chances are you know the person who made it. If it's a wooden table or chair, you might even recognize the forest it came from. There's a sense of wholeness, of connection."

Like U.S. dollars, local currencies are a legal form of taxable income. The Federal Reserve and the Internal Revenue Service have no prohibitions on local currencies, as long as their value is fixed to the U.S. dollar, the minimum denomination is worth at least $1, and the bills do not look like federal money.

BEGINNINGS OF A RENAISSANCE

The precursor of the resurgence in local currencies was a 1973 experiment in Exeter, Massachusetts by economist Ralph Borsodi. Fighting against the tide of inflation and Keynsian economics, he sought to demonstrate that people would use an alternative currency that did not devalue. With the cooperation of a local bank, a local newspaper and merchants, Borsodi issued the "constant," a currency that was based on 30 commodities and could be purchased with federal dollars at the bank. Many residents bought and used constants, and few redeemed them for dollars. They circulated for over a year until the nonagenarian Borsodi's health and age brought the experiment to close.

The next milestone for local currencies came in 1989 when a bank rejected the loan application of a delicatessen owner in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, home of the Schumacher Society. Robert Swann, the society's president, had helped Borsodi with the Exeter experiment. The organization advised proprietor Frank Tortoriello to issue "Deli Dollars" to his customers, who bought notes at $8 each for $10 worth of products at the shop. Dated to stagger redemption over time, Deli Dollars financed the relocation of the store without further debt.

The results showed how citizens investing in a local business through local currency think far differently from a loan officer feeding numbers into a computer. "His son had cancer and a lot of money that would have gone back into the business went to pay medical bills," notes Witt. "And maybe he's not as hard-nosed a business man as others. But anybody who's walked into the deli and watched Frank work knows he'll produce and do well. Instead of computer knowledge, it's human knowledge. It's a different basis for making decisions."

KEEPING CURRENCY MOVING

ALTHOUGH there are many success stories, some local currency programs founded over the past few years have reduced the amount in circulation or stopped issuing money altogether. The top factor is insufficient management staffing, says Susan Witt, executive director of the E.F. Schumacher Society and editor of its Local Currency News publication. Managing groups range from independent volunteers to community development corporations, from professionals to nonprofit groups. "We feel the ideal form is a nonprofit, membership-based corporation open to anyone in the region," Witt says. "A board of directors should be elected from that membership."

Manager burnout is the reason why Lehigh Valley Barter HOURS in eastern Pennsylvania no longer issues currency or publishes a newsletter. The Lehigh Valley Greens, an environmental political party, started the program on Earth Day, 1994. Modeled after Ithaca HOURS, at its height the currency had 100 participants, who received four free HOURS upon joining. The active program lasted through December, 1997, but never spread from the "friends of friends" stage to the larger community. "Frankly, you need a few people to be office workers," says Guy Gray, who managed Barter HOURS with Greta Brown. "We had a good little group that started the program, and when it lost interest, there was not enough energy among the larger group to take it over."

In contrast, Ithaca HOURS has received funding for a manager. In addition, a Municipal Reserve Group meets to determine how much money should go into circulation to stave off inflation, or too many bills chasing too few services.

Another pitfall for local currency programs is a lack of diverse services available. "The offers tended not to be basic, practical things," says Gray of Barter HOURS. "There were a lot of massage people and everybody with a computer thought they could do desktop publishing. We had one electrician and one person who did house repairs for Barter HOURS, but there wasn't enough to attract the larger audience that would want to know they could get real nuts-and-bolts services." Lack of varied services can dim the motivation to trade HOURS, reducing circulation.

The redemption areas for local currencies have to be small enough for the sake of convenience and a sense of identity. Most currencies are limited to one municipality or several small towns, but Barter HOURS covered Easton, Allentown and Bethlehem, the three main cities of the Lehigh Valley. "In Ithaca, it's one town instead of three cities, so people tend to meet at central places. We are all well meaning people, but we live in different parts of the valley," Gray explains. "We wound up seeing each other every two weeks. It wasn't central to our economic lives."

When local currency programs do falter, it doesn't mean they have to end. Even if no more bills are issued, locals can still trade among one another. Programs in places like Columbia County, New York and Halifax, Nova Scotia have encountered major difficulties and reorganized to try again. "There's no reason why Barter HOURS can't continue, given a couple of people who want to dedicate themselves," says Gray.

SUCCESS MULTIPLIES

The success led five other local businesses to start similar programs, as well as two farms that joined together to issue Berkshire Farm Preserve Notes. In 1993, the Schumacher Society organized the issue of a town-wide currency, the Berkshare, that would circulate only during a six-week period for each of the next three summers.

Shoppers received one Berkshare for every $10 they spent at participating stores, which paid $150 each to fund the program. On three consecutive days in September, consumers used Berkshares like federal dollars at stores for 25 to 100 percent of the purchase price of goods. Of the 75,000 Berkshares issued in the first year -- representing $75,000 -- 28,000 were returned. "That's an incredible return on a giveaway in a three-day period," notes Witt.

As she collected the notes, Witt encountered reactions showing how the currency galvanized the community. For example, one merchant who thought his customers differed greatly from those frequenting most other establishments was stunned to find how many different stores had issued scrip that wound up in his till. The promotion created a spirit of festivity, as people pondered the possibilities of how to spend their Berkshares. Residents going on vacation during the redemption period gave neighbors their currency, and customers at the registers chipped in Berkshares for those who came up short. "Merchants told me of a sense of cooperation among consumers that they normally don't see," says Witt.

Results showed how citizens investing in a local business through local currency think far differently from a loan officer feeding numbers into a computer.

Banks and merchants now are pushing for a currency redeemable throughout the year. Residents would put down $90 at a local bank and receive $100 in local currency. The response of the Bank of Boston to the program -- the only bank in town not locally owned -- is telling. "They said, `what you're proposing is completely opposed to our corporate policy,'" Witt recalls. "`Our policy is to make it as easy as possible for customers to shop anywhere around the world for anything they want. What you've suggested is completely contrary -- and we totally support it.' We're talking about human beings here, who happen to be bankers. They themselves are yearning for more connection to the community."And although the Berkshare program has been dormant over the last few years, the effects have been lasting. "What we found with Deli Dollars and Berkshares is that local scrip is an educational tool," Witt explains. "People become educated about the importance of shopping locally and begin making good decisions about federal dollars. It creates a general climate for more awareness of the need to support more mainstream local businesses."

ITHACA HOURS EMPOWER

After receiving a grant to Study ecological economics, Paul Glover decided to issue scrip in his home town of Ithaca, New York. (Six months after starting, he spent a week of research at the Schumacher Society's library of local currency books.) "I saw that environmental concerns often were pushed from the stage in the rush for jobs and profits, and that money did not care about ecology," says Glover. "So, investments were not readily available for ecological innovations. Therefore, we've started a money system with a regional boundary dedicated to the expansion of commerce that considers ecology and social justice."

Reinforcing trade within the town reduces transport of goods from elsewhere, therefore decreasing use of fossil fuels. "It also makes it easier to trace the environmental impacts of extraction, fabrication, transport and utilization," says Glover. "Also, by connecting people in a flesh-and-blood marketplace, where we become friends, lovers, and social and political allies, or resources, we reduce the social desperation that often leads to compulsive shopping. That may be a little abstract, but it's very relevant to a lot of what drives the manufacture of consumer goods. People often buy things to make themselves feel better, to fill a void, to feel more powerful. I think the role of the marketplace is to be a human intersection, not just a computerized abstraction."

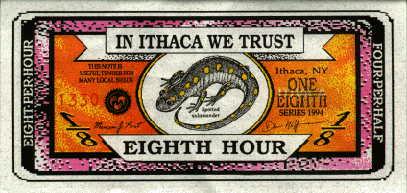

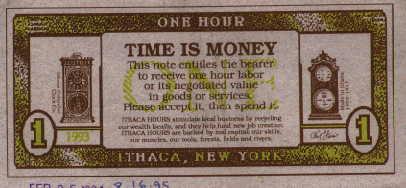

Glover started by signing up 90 people, showing them the prototype bill he designed. The basic unit, the Ithaca HOUR, is equivalent to $10, reflecting the ideals of a Sustainable minimum wage and pay equity (though professionals may charge multiple HOURS per hour). Ithaca HOURS are issued to residents agreeing to accept the currency, as bonus payments to those who remain with the program, as grants to community organizations, and as loans at zero interest. Five percent of the currency goes toward administrative costs such as printing, legal fees and publicity. The underpinning for Ithaca HOURS is HOUR Town, a bimonthly directory of goods and services that are available in exchange for the currency. The per capita supply of HOURS increases as more people accept them. "HOURS are backed by goods and services people will buy," notes Glover. "Dollars are backed by a $5.5 trillion national debt."

The program has issued, $66,000 in five denominations of Ithaca HOURS. It has grown to include thousands of residents and 370 businesses, including a bank, movie theaters, a bowling alley, health clubs, restaurants, farmers, plumbers, carpenters, electricians and a hospital. Many honor HOURS for their entire bill, while others accept them for a percentage of the cost. "We have transacted millions of dollars in value," notes Glover. "There's not only an economic benefit, but a cultural and human one because it helps us learn about each other as resources rather than competitors for scarce dollars. In the regional economy, at its best, everyone can have a unique and creative niche, while in the global economy, everyone is disposable."

Several hundred success stories published in HOUR Town have told of how the currency has supplemented household income, Made people feel less isolated, changed spending patterns, and given residents the satisfaction of getting paid for what they enjoy doing. The latest twist is the establishment of a health fund among local providers paid for in HOURS.

The next plan is a pilot program to make a major grant of Ithaca HOURS to the municipal government to supplement the incomes of human service employees. The government would then accept Ithaca HOURS for property tax payments. "The HOURS would go to employees, who could spend them at any merchant or landlord," Glover explains. "They would in turn accept local money because they could use it to pay property taxes."

STIMULATING SERVICES THROUGH TIME DOLLARS EDGAR Cahn started his own type of local currency, but don't look for any paper bills. In his Time Dollar program, service is recorded in a computer system and the hours redeemed for reciprocal services or specific incentives. His original focus was to reduce nursing home institutionalization by giving senior citizens a way to reward volunteers, but the idea has spread into a wide range of activities that build relationships among neighbors. Senior citizens, single mothers, the poor, the young, the disabled and the unemployed are being rewarded for beneficial labor within the community for which they wouldn't find compensation otherwise.In at least 200 communities and over 30 states, as well as England and Japan, people are tutoring, providing child care, housing immigrants, shopping for the elderly, counseling, doing community policing and performing other services for Time Dollars they can use to meet their own needs. The software needed to start is available for free at the Time Dollar Institute's web site (www.cfg.com/timedollar/).

The idea came to Cahn when he was hospitalized in 1980 and frustrated with being left "useless." "I thought of all the folks declared useless, whether they're young or old or in between," he recalls. "I thought about how I could link people with social needs together." Cuts in social programs spurred Cahn to action, so he studied at the London School of Economics for a year to prepare himself for issuing a local currency, He returned and attracted $1.2 million in funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in 1986 for three-year experimental Time Dollar programs in six cities: Miami, St. Louis, San Francisco, Boston, Brooklyn and Washington, D.C.

"The foundation concluded that they were very successful in terms of mobilizing people and creating social networks," Cahn says. "They didn't look like local barter systems; the dynamics were much closer to social networks. What this seems to do is empower -- it's what neighbors, friends and families always have done for each other. But rebuilding trust in a world where we all live as strangers to each other is an uphill battle."

Many Time Dollars are used among neighbors for services, but how they are spent depends on each local program. In Chicago, students are tutoring younger children and earning a free recycled computer after logging 110 hours. The program recently awarded its 1,000th PC and has produced positive changes in both the older and younger pupils. Elsewhere, Time Dollars are earned for food in Virginia, health services in Miami and public housing in Baltimore. Colleges, churches, neighborhood security patrols, state and federal social agencies and other groups are involved.

In Washington, D.C., where Time Dollar Institute is based, a health care group looked to Cahn for assistance in the community because he runs a legal clinic at the University of the District of Columbia School of Law. "They wanted a crack house gone and a school removed from the list of ones to be closed," he explains. Through a Time Dollar system arranged by Cahn, residents have earned $230,000 in legal work from a major law firm through an equivalent number of hours in services such as cleaning up a playground, campaigning for street lights and providing safe escorts. The work of the law firm and residents has improved the area, while the investment in the area has helped the law firm win major municipal contracts.

Cahn acknowledges that his program has much in common with local currencies that use paper bills, but maintains a certain philosophical distance from them. "We're all promoting local currencies and believe there needs to be a reward for sinking roots in the community. We have a lot in common in terms of values and agendas," he explains. "But I'm much more explicitly focused on social problems and class stratification -- the way this society treats people as one more throwaway disposable object."

Hard currencies used for commerce tend to devalue tasks performed by women, says Cahn, and can be spent for harmful things such as drugs or weapons. "I wanted Time Dollars clearly to be about people getting to know each other and trust each other," he notes. Keeping Time Dollars within the realm of social services also maintains their tax-exempt status, unlike other local currencies. "I don't want the government to have anything to do with this," Cahn says. "I have no problem with government giving seed funding as a way of dealing with social programs, but if it's not grassroots empowered, it's not going to work."

SPREADING THE WEALTHThe impact of Ithaca HOURS has spread far beyond the town's borders. According to Glover, there are 66 HOUR systems based on Ithaca's program. Many towns get started with a Home Town Money Starter Kit and video ($40 from HOUR Town, Box 6578, Ithaca, NY 14851; www.lightlink.com/ithacahours/). "Formal economic indicators tell us that things are going great and the economy is flying, but a lot of people are sinking further down, and that drags local businesses with them," says Glover of interest in HOUR programs. "We hear from businesses, chambers of commerce, nonprofit organizations and individuals -- everybody needs more money and more control of what money does."

Although many have been inspired by Ithaca's example, the founding groups and motivations for local currencies vary greatly. Differing origins include bartering groups, nonprofit initiatives, schools, community groups and service exchanges without paper money. Among the wide range of programs started in the last few years are Equal HOURS, from the $64 million nonprofit group Resources for Human Development, Inc. in Philadelphia, which runs 120 human service programs and has dedicated over $80,000 to the currency; Mo Money, from C.J. Peete Public Housing Complex Outreach in New Orleans, which circulates it only among the complex's residents; Valley Dollars, by Valley Trade Connection in Greenfield, Massachusetts, which grew out of the University Women's Network and is administered democratically by members at monthly meetings; and Hartsbrook School Scrip, an interschool discount program that raises funds for a nonprofit school through notes purchased at face value and redeemed with a five to ten percent discount at local businesses.

"There's not only an economic benefit, but a cultural and human one because it helps us learn about each other as resources rather than competitors for scarce dollars."

Sound HOURS have been issued in Olympia, Washington for South Puget Sound since 125 participants began the program in December, 1996. The idea grew from discussions within a group called the Sustainable Community Roundtable, which ordered Glover's startup kit. A grant covered the first issue of the HOUR Town on the South Sound bimonthly membership directory, which now has over 500 service listings. It currently is funded by a one-HOUR or $10 membership fee. With one HOUR worth $10, there were 1,000 HOURS, 2,000 half HOURS and 3,000 one-tenth HOURS printed initially (depicting the orca, the salmon and the heron, respectively). The amount issued has since doubled to $46,000 worth of HOURS.The currency circulates through the four initial HOURS given to new members and two to renewing members. Some have been sold directly at a 1:1 ratio to those who want to participate in the system, but lack the time or interest in offering services. Like the Ithaca program, five percent of the HOURS issued are reserved for the administrative costs of Sound Exchange, which manages the currency.

Only six to a dozen storefront businesses accept HOURS. The membership ranges from children who do yard work to construction contractors to music teachers. Many participants have business licenses, such as contractors and professionals who work out of their homes. Twenty vendors at a local farmer's market accept HOURS as well.

Sound Exchange sponsors events such as summer and winter

bazaars to publicize the program and give residents an opportunity to spend HOURS on products and services provided on site. In August, a benefit concert for Sound Exchange and other local community groups required admission in Sound HOURS. The take was divided among the organizations who helped with publicity and setting up, such as Energy Outreach Center, which advocates for alternative energy sources, Works in Progress, which publishes a local newspaper for radical causes, and Fellowship of Reconciliation, a group concerned with the rights of people in Latin America. In addition, monthly orientation meetings are held for new members to learn about the system and brainstorm about the services they might offer, and for current members to connect with each other.

Building acceptance is a slow process, says Stephen L. Beck, who maintains the membership database and publishes the directory. "When people think of money, they think of the dollar bill," he explains. "That image is a sacred icon; it's trusted implicitly. We have to build that trust gradually." Businesses are asked to accept a small portion of their bill in HOURS in the hope that the percentage will rise as their comfort level increases. The main selling points are the potential business from people who don't have much access to federal currency, the good will generated by participation and the boost to the local economy.

The economic effect has been minimal and difficult to track, but other dividends have been paid. "One thing I've noticed is that people use the directory as a phone book and seek out other members to do all sorts of things -- whether they use Sound HOURS or arrange a direct exchange of services without them," notes Beck. "These connections wouldn't have been established otherwise. Sound HOURS have served to knit the community together more."

For more information on local currencies, contact the E.F. Schumacher Society at (413)528-1737; www.schumachersociety.org.